Dr Gerald Pollack Electrically Structured Water – the fourth phase of water

Turns out, water has a fourth phase: H3O2

‘Our bodies are more than 2/3rds water by weight, and because the water molecules are so small they account for more than 99% of our total body molecules by count, so they must be important for something.’

In this re-release of his EU2013 Conference talk, Gerald H. Pollack, PhD, gave this one-hour presentation about the historical research and recent discovery of the electric charge within water on Saturday, January 5, 2013. We are taught water has three phases: solid, liquid, vapor. In 2003, Dr. Pollack and his laboratory group discovered a fourth phase that occurs next to water-loving (hydrophilic) surfaces projecting out by up to millions of molecular layers. Subsequent experiments show that this fourth phase is charged—and the water just beyond is oppositely charged—creating a battery that can produce current. Light charges this battery. Thus, water receives and processes electromagnetic energy drawn from the environment in much the same way as plants. This absorbed energy can be exploited for performing chemical, electrical, or mechanical work. Rich with implication, we are now able to provide an understanding of how water processes solar and other energies—and describe a simpler explanation of natural phenomena ranging from weather, green energy, and biological phenomena such as the origin of life. Professor of Bioengineering at the University of Washington, Jerry Pollack is an international leader in the field of water research. He received his PhD from the University of Pennsylvania in 1968.

Transcript

0:04

[Music]

0:11

I should actually call this the electric human because I want to talk

0:17

about electricity and not just water, but electricity. Let me tell you just how

0:22

we got started. It started with two famous scientists, one whose picture

0:27

you've just seen. But the first was Albert Szent-Gyorgyi and Szent-Gyorgyi maybe the father of modern biochemistry and a brilliant fellow with

0:40

wonderful quotes, he is highly quotable. For example, life is water dancing to the tune of solids.

0:49

He knew that water was central to all of biology. And then came Gilbert

0:54

Ling who's now in his 90s. This picture was taken long ago and he's written five

0:59

books since then. There were several major contributions. One of his contributions was that the water inside the cell was not like this water here,

1:09

it's actually water that is structured in some way, organized. The idea was

1:16

that, next to protein surfaces which are charged and have hydrophilic regions, the

1:21

water would build up into some sort of ordered structure, and that the inside of your cells and my cells were filled with water. And most scientists today

1:31

don't really think of water as being important. They think of water as

1:36

being well, as I said, just like that. However, we all know that we're two-thirds water approximately. And if you translate that two-thirds into the

1:45

number of molecules, because the water molecule is so small, more than 99 percent of our molecules are water molecules. So, they got to be

1:54

important for something. So, I actually took off on this. It wasn't so long ago, about 10 years ago, starting from Gilbert Ling and the idea that the water inside

2:05

the cell was critical to any kind of cell function. And I wrote the book and the book was

2:11

originally supposed to be to translate Gilbert Ling's ideas into plain English

2:17

and to try to expose them to the community. But I soon realized as I started writing that there was really more to it than what Gilbert had thought. But still the idea of

2:28

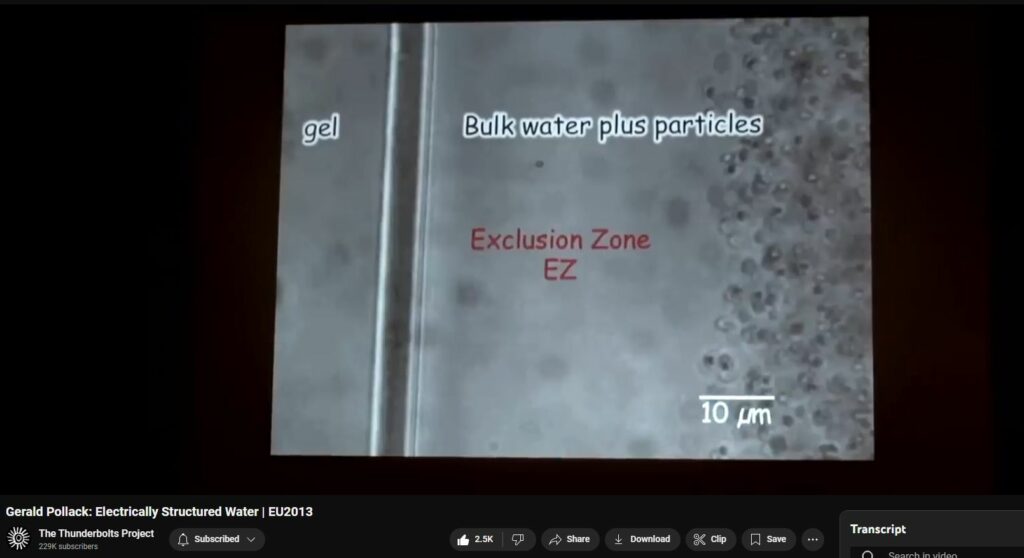

structuring of some sort of water next to surfaces was really important. By some serendipity we came upon an idea, to test the idea, of water structuring and

2:39

how far the structure might extend from the surface. And so, the idea at

2:44

first was a simple one. We took a gel - in this case it was a polyvinyl alcohol gel - and we put it into a chamber and we poured some water in, plus we put particles these tiny spheres,

2:57

microspheres in. Although later we used different solutes and got similar results. The idea that

3:03

Gilbert Ling brought up was that this kind of ordered or structured water would expel solutes. Just like ice. And therefore, if you want to find out

3:14

how extensive this region is, you can just see how far the region exists

3:21

without solutes or without particles. So, we did this experiment, and we found this

3:26

is the first time pretty much that we did it, that these particles were expelled from the region near the

3:33

interphase. They kept moving and moving and moving, and then they'd stop at about 50 or 60 micrometers from the surface. They would undergo thermal motion, moving

3:41

around, bouncing, but they would never enter back into the region, the clear

3:46

region. They were excluded and therefore we call this the exclusion zone, or EZ

3:51

for short. Another example of it is shown here. In this case we take a polymer, Nafion

4:00

and it comes in sheets. So, we just cut the sheet and placed the sheet down in the bottom of the chamber and add the water and the microspheres, and see what

4:07

happens. And this is what happens. The exclusion zone builds up - this video is cut prematurely – and it'll

4:16

extend out to something like three, four, five hundred micrometers. That's practically infinite by molecular standards, with huge numbers of water

4:26

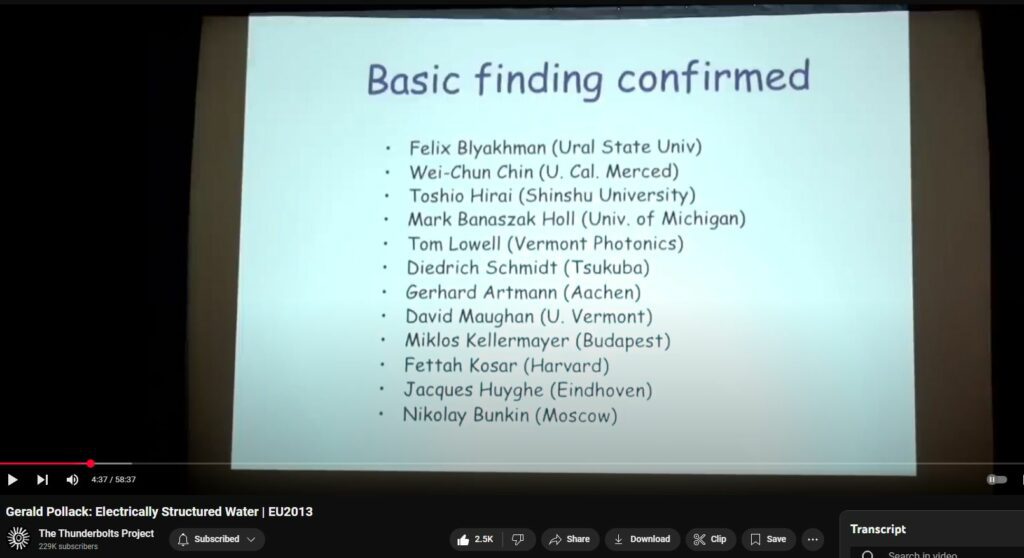

molecules in between. So, by now this finding has been repeated and confirmed by many people. In fact it was

4:38

reported in the Journal of Physiology in 1970 and it was a bit embarrassing to find out after the fact that someone

4:44

else had done it and got pretty much the same result. So, we know that these exclusion zones exist and the question

4:51

is what's really going on. The questions that I want to answer are first, is this exclusion zone

4:58

phenomenon general, or does it just apply to some polymers and a couple of gels? Does it really arise from the

5:05

ordering of water? Because if it did, it would mean a huge number of molecules ordered and this is against conventional thinking. Since creating order requires energy, where does the energy

5:18

come from to create this, if it really is ordering? And finally, what I want to spend most of the time on, can the

5:25

ordered zone help explain everyday phenomena? And by phenomena, I mean for

5:31

example, why the clouds exist as they as they do, and how come when you sprain your ankle, it swells very quickly? So, the first question is the one of generality. We've done a lot of

5:43

experiments and I don't want to bore you with all of them, but we've found that many substances show this exclusion

5:51

zone, as you can see here, including monolayers. By monolayers, what I mean, is

5:56

single molecular layers. So, you have a single molecular layer and some of this exclusion zone builds. Which means you need basically only a template. You don't

6:05

need something that has thickness to it. And among the solutes that are excluded

6:11

from this exclusion zone, it's not just the large particles that I've shown you,

6:16

but solutes ranging down in size to approximately 100 molecular weight. And

6:22

one example of that is shown in the next slide where we take a pH-sensitive dye.

6:28

Now these dyes are mixtures of molecules whose size is on the order of a hundred

6:34

or so molecular weight. And it's cool because they show you a local pH by changing color. This is an example of that. At the bottom is a piece of

6:43

Nafion similar to what I just showed you. And all the pretty colors that you see are indicating different pH’s. The main point of this slide is that the region right next to the Nafion

6:55

here, is clear, free of dye. So, it means the dyes are excluded and as I said the

7:02

dyes are approximately 100 molecular weight. What's even more interesting than

7:07

that is the color distribution. That orange color that you see just beyond the exclusion zone, means a pH of three or less. So, a lot of protons are sitting right next to that exclusion zone.

7:22

We'll come back to that because that's really important. In terms of generality, many hydrophilic surfaces generate

7:31

exclusion zones and many solutes are excluded from it. Okay, so question two is, is this zone really physically

7:40

different from bulk water? I've alluded to the possibility that it might be different, but I haven't shown you any

7:46

evidence. Well, I'm not going to show you a lot of evidence, because it would take a lot of time. But I'm just going to summarize most of the evidence and show

7:53

you some of it. And a lot of the evidence is published and the rest that hasn't

8:00

been published will be in my new book which should be out in two or three months. So, the first is that these easy water molecules are more constrained

8:10

than bulk water molecules. They're also more stable, we found from infrared radiation coming from it.

8:18

We found that the exclusion zone has a negative charge and I'll show you those

8:24

results. We'll come back to it since this is obviously central to the interests of everybody sitting here.

8:29

We found also that this zone absorbs light in the ultraviolet at 270

8:35

nanometers. That number is important and I'll come back to that one as well.

8:40

We found that it's more viscous than bulk water. We found that the molecules

8:46

in that zone are actually aligned in some way; and we found that the molecular

8:52

structure is somehow different from bulk water; and finally these are not our

8:57

results, but the results in two Russian groups who looked at the optical properties of the exclusion zone. And they found that the refractive index is

9:06

about 10 percent higher than that of bulk water. There are a lot of things that are different in this zone from bulk water, so it's clearly a distinct

9:15

zone. Now going back to the negative charge that I mentioned, the way we did this experiment,

9:22

is we set up a chamber and where it says ’inside’ that's actually the inside of a

9:28

gel. So, you have a gel sitting there which in this case is a polyacrylic acid

9:34

gel, and ‘outside’ refers to outside the gel where there's water. So we took two electrodes. These are

9:43

microelectrodes that taper down to less than one micrometer, and we put one out

9:49

here somewhere as a reference, and the second one is sitting here and so we move it point by point towards the

9:55

interface. And here's the distance scale and if you're far enough away from the interface, the potential difference

10:02

between here and here is zero. That's comforting, that's what you expect, but as

10:07

you get closer and closer, you begin to pick up a negative electrical potential which goes down to minus 120

10:14

millivolts. So, the region of negativity seems to correspond roughly to the

10:22

position of the exclusion zone. It looks like the exclusion zone might be negatively charged. Now, we get rid of the gel and put a piece of Nafion on there

10:32

instead, and repeat the experiment. The result is qualitatively similar but quantitatively a bit different.

10:39

The region of negativity extends farther out from the interface, but please remember that the exclusion zone is bigger in the case of Nafion. So, there's a correspondence between the region of

10:52

negativity and the exclusion zone. It looks as though the exclusion zone is negatively charged.

10:59

But that doesn't really make sense if you think about, it because what you've done is you've taken some water

11:04

and you've poured the water in and the water starts out as neutral. So how do you start with neutral water and wind up with a fairly large, negatively charged zone?

11:15

Well, the only reasonable way you can do that is if you have a positively charged

11:20

zone somewhere else. And the question is, is there any evidence for a positively charged zone somewhere else?

11:27

And the answer is yes. If you look at the previous slide that I showed you, (it's turned 90 degrees for

11:36

convenience) and realize that you do have a negative zone. But remember, the red color indicates a huge

11:43

number of protons. So, it looks like you have negative here and positive here. So, the two seem to be in balance. And just to check to see whether it really is

11:53

charge separation, we put one electrode here, one electrode here, and connected them through a resistor. So, if there's charge separation you should get current

12:01

flow. And indeed, that's what we found. So, the current starts at a fairly high

12:08

value and goes down, not to zero but to some plateau value which extends over

12:13

some time. So, it really looks as though there is definitely a charge separation

12:20

between the exclusion zone and the region beyond. So really what we have is what looks like a

12:27

charged battery in water. And of course you don't expect a charged battery in water, but it appears

12:34

from the evidence that's what we found. Now, one expectation of this, which we checked, is that if you

12:42

have separated positive and negative charges, you should have a force between the two, because the two want to attract each other. And we actually tested

12:50

recently, to check, to see, whether there is this kind of attraction. And we did it

12:55

by setting up a lever which you see up at the top, a ribbon-shaped lever, and we

13:01

put a piece of Nafion attached to it. If you look at the second panel, you see what we expect

13:07

to happen is that we have a negative exclusion zone here, and you have the positive charges that are out here. There should be a force between the positive

13:16

charges and the negative charges that are attached to the Nafion. The exclusion

13:21

zone is practically bound to the Nafion. So, we expect the beam to deflect. And indeed, that's what we saw. As you put the water in, the exclusion zone builds and the

13:31

beam deflects. So, it looks as though there really are charges genuinely separated between the

13:38

exclusion zone and the region beyond. So, I've just shown you that the exclusion zone has negative charge

13:45

and positive beyond. So now if you want to figure out what's going on in this exclusion zone,

13:53

all of these are clues. But the three clues I think that are the most important, starting from the bottom,

13:59

the blue ones, is that the exclusion zone molecules are aligned and they're fairly

14:05

stable and they're constrained. If you put those together, what fits most

14:10

closely is some kind of liquid crystal. So, it looks as though this region is a liquid crystalline region, as opposed to the bulk water which is a liquid. So far,

14:20

what I've shown you is that you have a liquid crystalline region of some sort; you have negative charge in this region; this region excludes solutes profoundly, unlike bulk water;

14:33

and there's some hint that it's non-dipolar because of reasons that I'll go into in a moment,

14:40

not just a stack of dipoles and it may extend very far. By very far we're talking not the two or three molecular layers that the chemistry books will tell you, but if this is right

14:52

it's two or three million molecular layers that we see. Now it was suggested

15:00

101 years ago by Sir William Hardy that there might be a fourth phase of water.

15:06

So, we think of solid, liquid and vapor. But there were many reasons long ago, forgotten, that led to the suggestion that there might actually be a fourth phase. Whether this is a

15:17

fourth phase is up to you to decide or judge, but all of the physical and

15:22

chemical properties of this zone are different from either solid or liquid. Now what about the non-dipolar

15:31

structure? Well, my hero Gilbert Ling, the second person I showed you, suggested a stack of dipoles.

15:37

But as we began to look at this, we realized that that model is not adequate. The reason it's not adequate is

15:45

first of all, that this zone has negative charge, it has a lot of negative charge. Dipoles are neutral so it doesn't

15:52

matter how many dipoles you build up stack you still get neutrality so that

15:59

is that doesn't work. The second reason is that this 270 nanometer absorption of light in the exclusion

16:06

zone, usually that kind of absorption is not associated with dipoles. It's

16:12

associated with ring-like structures, so that's a second reason to doubt the stacked dipole. Well,

16:20

if you want to figure out what the structure might be, where do you start? Well, the way we started is by

16:27

saying, probably the structure of this zone should have some precedent. It should be built on some structure that

16:33

we already know about. So, what kind of water structure do we already know about? That's ice. Okay. So, there's a picture of a model of ice on the left side. These are just two different views of

16:46

the same structure. The red dots are oxygens and in between the two oxygens would be a hydrogen. It's just omitted to reduce the clutter. Now, if you look on

16:55

the right side, you see these blue dots between the red oxygens and these blue

17:02

dots are protons. Positively charged protons. And so what you have is that the negatively

17:08

charged oxygens are, you might say, glued together by these positive protons and that's why ice is hard. So, we thought maybe some variant on the ice structure

17:20

might be adequate to characterize the the exclusion zone and so the first idea is well, you know, let's just

17:27

remove the protons and if you remove the protons from a neutral structure, which is ice, take away the positives,

17:34

and then you get a negative, net negative charge. And that's good because that's what we want.

17:41

And also, it's a non-solid. We don't want a solid. We want something that maybe has viscous gel-like properties. So, it looked like a great idea until we realized, scratching our head,

17:54

that it won't work. The reason it won't work is that if you take away the positive charges connecting two

18:02

negatives, then you have two negatives juxtaposed next to each other and the structure would just fly apart. So, a great idea but unfortunately it didn't work.

18:11

So then, after a bit we thought here's another idea. It's very similar but slightly different, which worked nicely.

18:19

Take the two planes, shift one relative to the other by half of the oxygen-

18:24

oxygen distance. Then you get something that's very nice because what you see is that you have the oxygen in the back plane negative, juxtaposed next to the

18:35

blue hydrogen which is positive. So, you have electrostatic sticking. So, there's these planes that stick together nicely but not as rigidly as in ice. So, with

18:44

this structure you have a situation like this, where you have a material, it's sitting in water and from the water the water molecules somehow build these easy

18:54

layers that stack on one another, one at a time, growing like this. And so that would be one way to account for

19:04

this kind of structure and if you look at one plane of this structure, it looks

19:09

something like this. It’s a bit like ice, but it's not exactly ice. However,

19:15

if you count the number of oxygens and hydrogens it's not H2O, it's actually H3O2. So, you might say that this

19:25

zone of water, it's water but it doesn't have the same chemical formula as water,

19:31

slightly different, like H2O2 for example, hydrogen peroxide. Same molecules but in a

19:37

different ratio. And it's that ratio that confers the negative charge on this zone. Now,

19:44

in constructing it, I took the top plane and moved it to the right relative to the bottom one but there was nothing sacred about moving it to the right. I

19:52

could have moved it to the left, or I could have moved it 60 degrees, or 120, because of symmetry and I would have gotten pretty much the same result. So, the ability to shift in each of six

20:02

directions gives a lot of latitude. For example, you can build structures like

20:07

this, helical structures. And so, here you've got layer zero; the first layer

20:13

shifted this way by zero degrees; 60 degrees; 120 degrees; giving you a helix.

20:18

So why is a helix important? Well helix is important because, as you know, in

20:23

biology most of the molecules are the fibrous proteins. For example, in DNA and RNA they're all helical and it's known that these entities are surrounded

20:33

by some kind of ordered water. So, it's possible that this creates a nice interface with those molecules.

20:41

So, the advantages of these sheet-like layers that stack is that, first of all, it's not pulled

20:51

from a hat. It has precedent. It has negative charge which is what we need.

20:56

The ring-like structures are more able to delocalized electrons to explain the

21:01

270 nanometer absorption that's observed. It's able to accommodate helical structures.

21:07

And an important one for chemists, that the large sheets eliminate the Brownian

21:13

instability. Now, what do I mean by that? Well, if you look at the structure on the left which you may

21:19

think of as stacks of dipoles, you know, each dipole undergoes some kind of thermal motion and if you start

21:27

stacking them, the thermal motion builds and you can't build more than six or seven or eight or ten. Various chemists

21:33

have said therefore this kind of structure is impossible. We're not suggesting (there are arguments

21:39

both ways), we're not suggesting this structure. We're suggesting a structure that has practically infinite extent,

21:44

something like this. And when you increase the mass, the Brownian excursions diminish, based on the mass. So

21:52

we have something here that undergoes very small Brownian motions and each layer is effectively glued to the region

22:01

next to it. So, the issue that you can't build many layers because thermal motion will make it impossible, vanishes.

22:10

Now, so that works. Another one is that the tight lattice keeps the hydronium ions out. So, what do I mean by that?

22:20

Well, we've got charge separation here. We have an exclusion zone that has a lot of negative charge and we have a region outside that has positive charge, and as you know, when you have negative and

22:31

positive they want to do that. That doesn't happen or it doesn't happen very much, because we can put the

22:36

electrodes in and you can put the electrodes at time equals five minutes, or one hour, or three hours, and it's

22:43

pretty much the same. So, how is it possible that those positive charges - which are actually not protons,

22:50

they're protons latched onto water molecules to give hydronium ions which we all learned about in freshman

22:56

chemistry – don’t move? Those hydronium ions really want to get desperately to move

23:02

into here, but they can't move in. They don't move in, that's the observation, and so why don't they move in? Well, they

23:07

don't move in according to this model because this lattice structure is so tight. The hexagons themselves are

23:15

small, but the hexagons are shifted relative to one another. So, the real openings are extremely small. so they

23:21

can't get in, they keep separated. So, the battery charge remains separated. So, another advantage: this tight lattice

23:30

keeps the hydronium ions out. So, it looks like there are a whole bunch of reasons to think that this model

23:38

is reasonable, but you might ask well, okay it's reasonable, but give me some evidence, does it really exist?

23:45

There are actually quite a few papers demonstrating hexagonal types of water near interfaces, but most of them deal

23:52

with only a few layers because of the methods that have been used. But there's one method that goes more deeply

23:59

and that's shown here. The paper was published by a Harvard group in 2008 and they studied the protein ATP synthase-

24:07

subunit C of that protein. It's a very old protein; it has an interesting character to it. What happens is that

24:14

when the atmosphere is dry, it forms vesicles that you see for example in the top slide that enclose the water. You

24:22

have a volume of water enclosed in this, either circular vesicle that you see at the top, or

24:28

different geometric shapes that you see here. But these are volumetric structures. So, what these investigators

24:35

did was to take an electron beam and do diffraction on the water, the volume of water in between, and the result was

24:43

interesting. It's a series of dots and the dots mean that the water is very well-structured and the fact that you

24:50

have six dots around here, means it's a hexagonal structure. So, they concluded that the water inside these capsules are

24:58

ordered hexagonal sheets of water. So, the answer to question #2 is the EZ physically distinct from the bulk?

25:06

Yes, it's distinct and it looks like it's a layered honeycomb structure. Okay, so now I presented to you this

25:13

battery that we have, and as you know batteries usually need charging or recharging, and the question is

25:21

what charges this battery? We couldn't figure this out for a few years. We scratched our heads

25:31

and finally we found out that in fact it was radiant energy – light. So, light charges this battery and we found

25:41

out actually from an undergraduate student who was walking around. We had the chamber sitting here and the

25:47

undergraduate student had this light and was shining the light. And we saw that where he shined the light, the exclusion zone was building, actually rather impressively. Something like you see

25:58

here. Here are the microspheres here's the exclusion zone and this is the region that was illuminated. You

26:04

take the light away and the EZ comes back again. We found also (I won't show you the data,

26:09

it's published spectroscopic information), we found that the most powerful wavelength among the wavelengths we

26:16

studied, from UV to infrared about five micrometers, was the infrared, especially at three micrometers. And we would shine

26:25

the infrared with a small light-emitting diode that emitted the infrared and we could get an expansion easily of 10

26:32

times. You take it away and it comes back again to its original position. Now, where do you get

26:40

infrared? Well, we're all familiar when you turn the range on and it gets hot, and it emits infrared. But in fact

26:46

everything around us emits infrared, it's you might say, a gift from the Sun or the stars, the cosmos, hitting the

26:55

building and re-radiating on the walls and such. So, this is essentially free energy, literally free, it just comes

27:02

to us. And this is the energy that goes into the water and builds the exclusion

27:07

zone. So, effectively you have a situation like this. You have a material and water

27:12

next to it and this EZ water from the energy that comes in, many wavelengths, but infrared is the most important. It

27:21

builds up like this and if you were to take away the excess energy, it would come back. We also found a way of

27:27

diminishing the ambient infrared energy. This took us, embarrassingly, a while to

27:33

figure out. But if you take a simple Starbucks, a coffee container, it insulates right? And so, what does that

27:41

mean to insulate? It means it blocks the infrared from coming into your iced coffee and warming it up. And so we took

27:49

a dewar, the same sort of thing but a professional one, we stuck the chamber with the exclusion zone inside.

27:55

So this is the result. The top one is the control. You can see a standard size exclusion zone.

28:01

And then we put it into the dewar for 15 minutes, took it out and quickly looked before it built up again. You can see

28:07

that the exclusion zones on either side are smaller, roughly half the size, and then pull it out and let it sit on

28:15

the bench and they build up again back to the normal size. So, it means that we can either increase the energy or

28:22

decrease the energy and it has a direct effect on the exclusion zone. So the answer to question #4 about energy is

28:30

that EZ is powered by photonic energy which orders the water and charges the water battery. Now, what about energy flow

28:39

on the Earth or the solar system. So, the Sun hits the water and generates heat, we all know

28:46

that. However, I've shown that it imparts energy for building order and separating charge. Now if that's true, then you might

28:55

ask okay, if it's building up this potential energy, can you get the energy out after you put the energy in? And we

29:02

found that you can. We found that again, a couple of undergraduate students found, if you put a tube made of some

29:11

hydrophilic material, either Nafion to start with, or gel that you get constant flow through the tube. And the experiment

29:18

is shown here. You take the tube and you quickly fill it with water to make sure there are no air bubbles.

29:27

Put it in the water bath that also contains microspheres so you can see if there's any movement. Put it in the

29:33

microscope and the result is shown here. So, you have a flow and the flow keeps going and it's not just the

29:40

Nafion tube, we found the same thing occurring in a gel. We cut a tunnel inside a gel, a cylindrical tunnel, and

29:50

you can see here that there's an exclusion zone and right in the center are all the microspheres. And the video

29:56

shows what happens, that you've got constant flow through there. Recently we tried to see if we add

30:04

light do we get additional flow? We found that we can actually increase the flow by up to five times by adding light. So,

30:12

this is flow that's basically free for the taking and it's powered by light. Essentially it means that this

30:20

is doing work by driving it through because the water has some viscosity. So, if work is done if

30:28

the conservation of energy works, if then the system must be absorbing energy. And I suggested to you what

30:40

the energy is: it's the electromagnetic energy that is coming in to give the potential energy to drive the work. So

30:46

water transduces light energy. Now, again if you're not Rupert Sheldrake, you'd think this is weird. However,

31:01

if you think about it, think about the plant that's on your windowsill, it’s doing the same thing. It's

31:08

taking light energy and transducing that light into chemical energy which does drive metabolism, bending, growth, what have you.

31:16

And so I'm suggesting to you that the same thing is happening in this glass of water, right here. The energy

31:25

is coming in and it's getting transduced into some kind of potential energy from which you can get a lot of interesting

31:31

things, some of which I don't have time to talk about. So, that leads to the equation, and I know the units don't match,

31:41

you can't really think about water without thinking of energy. Somehow there's energy that's getting into this, and

31:50

this energy, again I don't have time to suggest to you, but some of this energy may contain information. That's

31:57

another story beyond this. I want to give you five examples briefly. The first example is the cloud. Okay, so for the

32:07

cloud the question arises, you have water that's evaporating from all over the place so it's not only

32:13

evaporating from just under the cloud, it's also evaporating from here. And the question is, well how come there's no

32:21

cloud here, or here, how come there's this one here? It appears that the water molecules are somehow evaporating coming,

32:26

you might say condensing, but what brings those water aerosol droplets together? And I'm going to suggest to you next

32:35

few slides that you'd expect them to repel each other, but actually they come together because of the so-called ‘like

32:41

likes like’ mechanism. They like each other so they come together. So, just to explain that, here is a summary of what

32:49

I've shown you. If you have a charged particle or molecule in water, you have this liquid crystal EZ water around it,

32:57

negatively charged, and you got a lot of protons or hydronium ions spread all over. And this is powered by

33:05

electromagnetic energy. You won't find this in the textbooks of course, but anyway, just remember

33:12

this and suppose we have two particles now, instead of one. And suppose they're both negatively

33:17

charged. Well, the reflexive response is, oh, they're both negatively charged so therefore they'll repel each other and

33:24

they'll move in this direction. However, they actually move in this direction, and this has been shown

33:32

almost 100 years ago by Irving Langmuir, and then Richard Feynman in his lectures was talking about this. And

33:38

Feynman in his own inimitable way called it ‘like likes like’, that is like charges like each other, so they come

33:47

closer together. In fact, you can find something similar which comes from the tale of Genji about warring parties

33:56

fighting against one another. The only way to bring these parties together is to put something attractive in between.

34:04

Yeah, I'm told this is in the tale of Genji. So, that's what happens here and until recently, you know, Feynman said ’like likes like’ because of an

34:14

intermediate of ‘unlike’ charges. And here are the unlike charges, bringing them together and the stability occurs when

34:21

the attractive force is equal to the repulsive force between the two negatively charged entities. Then they're

34:27

stable and if they're stable if you have a lot of them, then they're going to be in this situation just like this.

34:33

This is well observed by many groups, over many years. It's called a colloid crystal. It's like if you may have

34:41

had yogurt this morning, probably the yogurt that you ate, had the consistency that it has, because of these

34:49

opposite charges that keep the particles basically in balance. They stick together because of

34:55

like likes like and I'd like to suggest to you that's what happens in the clouds, that the aerosol droplets all have

35:02

negative charge. And what's holding them together are the positive charges in between, giving you ‘like likes like’

35:09

attraction and, if they're ordered, you can get rainbows out of this. Okay, next point: sand castles. Well, you know that

35:19

you can't build sand castles out of sand, you need sand plus water. So, what's going on with the water? So, what happens is that you

35:28

see the sand particles up there, each sand particle, silicon dioxide, builds an exclusion zone right around it,

35:34

negatively charged, and in between are positive charges. So, you have attractive forces because the positive attracts the

35:42

negative. It brings all those particles together and glues them together, so you can build sand castles to protect us

35:48

against invading flotillas. Okay. Ice. We find this all around the cosmos, and there's a paradox that I'd like to

36:03

start with. I'd like to talk to you about how I believe ice forms. The paradox is that usually if you want to create

36:10

order, you have to put energy in. It's like cleaning your room, you know. It's easy for the room to be messy, but it

36:17

takes energy to restore it to it's ordered state. But in the case of ice, it looks like [when]

36:26

you put it in the freezer, it pulls out energy. So, it seems to be the opposite. How do you get

36:32

energy withdrawal? It seems to be philosophically or thermodynamically opposite what you expect.

36:38

Does ice really violate the general rule? So, let's look at how ice might actually form.

36:47

So this is ice, you saw this before. As I showed you, the ice structure is very closely tied to the EZ structure.

36:54

There's a slight difference. You just pull out the protons, remove the protons from ice and you get the exclusion zone. So, these are very close together and the implication is, if you want to get

37:06

ice, you just have to start with the exclusion zone and re-add the protons. So, this is a reversible situation.

37:14

The exclusion zone, being so close to the structure of ice, looks like a possible precursor of ice.

37:22

In other words the hypothesis is that in order to get to ice, you don't start with bulk water, you go

37:29

from bulk water to EZ water and then to ice, because those two structures are very close together.

37:35

And so, it would work something like this. You start with the EZ structure, right? And then you add protons in between

37:43

those two layers and then the layers undergo a bit of shift as you see here, and you get ice. So those two are

37:51

very close to one another. So, now the question is, is this hypothesis borne out by evidence,

37:58

is the EZ really necessary for ice formation, and I'm going to show you that it is. And so, this is one of several

38:07

experiments that we've done to demonstrate that. You see a cooling plate down at the bottom and a strip of

38:14

Nafion sitting there, and we put a droplet of water right next to the strip of Nafion, so everything gets colder and

38:21

colder. You see the region of view in the next slide. So, we're getting colder and colder and starting

38:28

to freeze. And what you see here is the piece of Nafion and here's the water drop, and this bright region is

38:36

the first region to freeze. We always get freezing right at this interface. Now it begins to spread and you

38:43

can see it's beginning to spread in this direction and you can see down here that it's spreading right in the exclusion

38:49

zone before it actually goes out here. So, it looks like the exclusion zone is the first to freeze. In other words, it

38:56

is the exclusion zone that undergoes the change to ice. So, the scheme is something like this, where you have an

39:03

exclusion zone and next to the exclusion zone are the protons and they keep building up, you see here. What

39:11

happens next is they actually rush in to the exclusion zone. Remember you need protons

39:19

plus exclusion zone to create ice. And so, basically you have ice formation right here. And the process keeps repeating and

39:29

gradually you build up more ice from the exclusion zone plus protons. So that's the scheme. Now does this really happen?

39:37

And here you can see one experiment that we did to demonstrate. This is a chamber and it's

39:44

got some microspheres here and we start cooling this cooling plate. It turns out that next to the cooling plate

39:51

we get a very big EZ here and we put dye in. The question is, if we put dye in instead of the

40:00

microspheres, is it true that we see a pH change here, indicating that there are protons that are rushing in? You can

40:09

see the result here. It shows that this zone that just freezes turns red. Red means a lot of protons in here as I've

40:19

shown you before, so it looks as though a lot of protons are rushing in during the time of freezing.

40:26

Another experiment that shows the same thing. We have a cooling plate here, a little dish with water

40:34

and pH dye. This means a neutral pH. So, we're cooling from here and gradually this gets colder and colder and it

40:42

starts to freeze. It starts to freeze around the edges and you can see the color around here has gone from the

40:49

green to this red orange and the pH here corresponds to pH=3, this is a huge number of protons. The same with a droplet

40:59

that's undergoing freezing. So here it's neutral, it gets colder and colder and you can see the red color during

41:05

freezing. So, it's clear that ice formation absolutely involves protons. And thus, ice formation is the

41:16

exclusion zone plus protons [together] give you ice. And so, I think the energy paradox is actually resolved, when you think of

41:24

this process that's going on. Because you're starting with an EZ which is a liquid crystal,

41:31

so it's moderately ordered and the ice is more ordered. So, if you need more energy to get more order, you actually

41:39

get the energy because the charge separation is potential energy. So, you're adding this potential energy to get

41:46

something that's more ordered. So, there's no violation of any thermodynamic principle.

41:53

Increased order does require energy. Now, in the reverse case, if you need EZ water to get ice, then if you melt the

42:02

ice, you should get EZ water. We tested that and we got exactly that. Melting should produce EZ water. In

42:10

a little cuvette we put some ice and we gradually let it melt and we looked at the water that was forming during the

42:16

melt. And, if you remember EZ water is tested by looking at this 270 nanometer absorption.

42:24

So, here's what we found in the melting ice. There are four graphs and each one is a different kind of

42:33

water, deionized, distilled etc. and you'll notice that they all have peaks at 270 nanometers. Ordinary water

42:41

doesn't have that. Okay so now (getting there, almost there) low friction. Why is there friction to start with. Well

42:53

friction is caused by asperities like mountain tops. If you shift one by the other you get friction.

43:02

If you have two surfaces that look like this, a bit ragged at the edges, and they're hydrophilic surfaces and you add water.

43:11

Now what happens when you add water? Well, you have an exclusion zone here, an exclusion zone here, and

43:18

positive charges, hydronium ions, here. The hydronium ions repel each other. They push the surfaces apart, therefore, if

43:25

your shear back and forth, you ought to get very little friction. And people have demonstrated exactly

43:31

that with polymers. Very little friction. Now, what about ice, what about ice skates? Well it's been known since Michael

43:39

Faraday that on top of ice, there's a liquid layer. And you'd say, well if you have a liquid layer, friction should be

43:47

reduced. But I think it's more than that. It's possible that this layer that we're talking about, contains EZ plus protons.

43:56

Because I just showed you that when ice melts, it gives you EZ. And together with EZ you have protons. So, you have a

44:03

lot of protons sitting beneath that skate, and remember those protons are repelling each other. So, therefore the

44:10

skate blade is repelled, it keeps away from the ice, and that's why the friction is as low it as it is. You can

44:17

imagine also that the more pressure you put on, the more protons you get. So, you put on pressure, you squeeze out those

44:25

protons. You put on more pressure, you squeeze out more protons, and the more protons you have repelling, the lower the

44:31

friction. So, the ice skater bears down really hard and the friction goes down. Therefore, you have low friction.

44:41

Biological applications. The last one. Here's a question for you. How come when you do deep knee bends,

44:50

you do this with almost no friction? Now I've got a lot of weight pressing down on my joints. So, why is that? Well, if you

44:57

look at the anatomy, the principle is actually very similar. You have a bone here and a bone here, and

45:04

in between is a so-called joint capsule. And here you have cartilage which is basically a gel, and here is cartilage

45:12

which is basically a gel. So, next to the gel you should have an exclusion zone here, an exclusion zone here, and protons in between.

45:21

So you expect a lot of protons in between and I just suggested to you what happens when you have the protons.

45:28

They repel these surfaces and people who are doing experiments on these joints report, incredibly, that people bear down,

45:37

but they don't touch each other. The two surfaces remain some distance apart and nobody can figure out why. And I'd like

45:44

to suggest you that the reason your joints don't squeak, is because of those protons that are held in that joint

45:50

capsule. Now okay, so what happens now when you sprain your ankle? I don't know if you ever noticed those

45:59

of you who broke ankles, or if you look at your leg or your elbow. I've been through it.

46:06

The swelling occurs not in 30 minutes or so, it occurs in 30 seconds or less, 10 seconds. It immediately swells, so how

46:14

does it immediately swell? I think this has something to do with what we've been talking about. The

46:21

tissue that we're talking about in there is either connective tissue, muscle tissue that's inside around those

46:27

joints. Now, if you look for example at muscle tissue; this is a scanning electron micrograph of a muscle

46:34

and the muscle is running lengthwise this way, and you can see (these are mitochondria by the way) you can see

46:41

cross connections between these. Now if you look at the fine structure of these myofibrils (we studied muscles for 30

46:48

years), it looks something like this. Here are the protein filaments and notice something interesting.

46:55

These protein filaments are all cross-connected, they're like rungs of a ladder. So, the situation looks something

47:02

like this. Now these are hydrophilic proteins that run this way and they're all cross-connected.

47:09

Now when you have a hydrophilic surface, you know what happens. The water layers start building up here, they start

47:15

building here, the EZ layers and they want to expand the structure. But they can’t expand the structure

47:21

because of these cross links, and that's why your muscles or your tissues don't expand. They have only relatively

47:29

little water in them, it's only two-thirds water. Other gels are 95% water. It's because of these cross links that

47:36

don't allow it to expand. However, if you have an injury and you tear the tissue, what happens is that these

47:43

cross links break, and if they break then these EZ layers can pile up with impunity. They just build up and I'd like

47:51

to suggest to you that without that restraint to swelling, that's what happens when you sprain your ankle, or

47:57

you break your ankle. You get this because the EZ layers build up within seconds or minutes, and so the swelling

48:05

arises from that. Okay, finally the last three minutes or so. Is that okay? Oh I'm okay and I can relax a little

48:13

bit. Thanks, I was hurrying. Now I'd like to talk about calories taken in versus the amount of energy that gets used.

48:24

See, it's not just the food that we eat from which we get energy, it's the radiant energy that

48:31

comes in. We're full of water, and I'm receiving radiant energy all the time from outside, from the light

48:39

here, that light and the walls, and of course plants use this energy to their advantage. And the question is, can we

48:47

make use of any of this energy, of this received light energy? If you take your hand and you shine a flashlight

48:53

in the dark, you can see the light coming through. So, some wavelengths do penetrate pretty far and the question is whether

49:00

we make use of that energy? And one possibility, a place where we might make use of it is in the cardiovascular

49:07

system because the vessels are pretty superficial. Now, obviously the heart is pumping and generating pressure in our

49:14

arteries and whatever, but when you get down to the capillaries, you have a bit of a problem. So, the red blood cells look

49:20

like this and they're typically six or seven micrometers in diameter. For young people the capillaries, the

49:30

smallest vessels, are actually less than six or seven micrometers. Some of them are as small as three or four

49:37

micrometers. If you're a mechanical engineer, you're not going to design the system this way, where you try

49:42

to take something big and stuff it through. But that's actually what happens and the question is whether there's

49:48

enough energy from the heart to actually drive it through. My Russian colleagues have done some calculations,

49:54

I'm not sure if they're right. They calculate that, if the heart really pumped the blood,

50:01

forced it through those narrow capillaries, the heart would need to develop 10 to the sixth times the

50:06

pressure that it actually develops, because the resistance is so high in those vessels. So, the question is whether

50:11

maybe there's some other energy that helps that. If you look at some vessels inside of muscle tissue, you

50:18

can see that the red cells are distorted. They're bent, they have to squeeze through, they don't just sail right

50:24

through like that. Some are actually retarded quite a lot in in their passage. The question is whether it might

50:31

be that this gets some assist from the energy that's coming in from outside. Now that would seem a ludicrous

50:39

idea, if I hadn't shown you that you actually see it in the laboratory. We have a hollow tube, a hydrophilic tube,

50:47

just like the vessels sitting in water, and I've shown you that the radiant energy that comes in, is driving the flow

50:54

through vessels. So, I raise the question. No answer. Might radiant energy help drive your blood flow?

51:01

Might we take the absorbed external radiant energy in assisting with that? So, this is actually more general than just

51:10

the cardiovascular system, you know, because in cells (of course the cells are much

51:17

more crowded than I've shown here) but around each protein will be an EZ, negatively charged, and in the water

51:23

that's beyond that it'd be positively charged. So, you have negative charge and positive

51:28

charge separated from one another. And all the reactions that occur in the cell require either a negative charge or

51:35

positive charge, they're reduction or oxidation reactions. So, what you have is basically a ready-made system to

51:42

drive those reactions. And the energy for that can come from ambient radiant energy or heat energy generated by other

51:52

regions in the body. In fact, all those protons that are generated is very [familiar] to some of you who know biology,

51:59

about mitochondrial proton pumps. This is a proton pump and you get it free in a very simple way. So, separated charges drive reactions.

52:12

I think the exclusion zones are central for biological function and just the last moment I want to mention two things.

52:19

If the EZ’s are central to biological function, then what wipes out biological function, at least temporarily? Well, anesthetics do,

52:29

anesthetics block all nerve conduction and many other aspects. We did some experiments. I'm not going to show you the data, but I

52:38

don't want to keep you too long, and we found that in clinical concentrations the anesthetics, two local anesthetics,

52:45

bupivacain and lidocaine diminish this zone and bring it to zero, in clinical concentrations. And in the

52:52

reverse, aspirin, salicylic acid, which improves function, you know if you have a headache it goes away. If you have

53:00

soreness, goes away, if you have fever, goes away. You take aspirin, it's good for you, so we thought well, maybe

53:06

aspirin actually increases the exclusion zone and sure enough, that's exactly what we found. I'm not going to show you the

53:14

data. The experiments are ongoing, but they show it. So, I think that the EZ water is central to all

53:22

biological function which is what I suggested in that book, new book as I said is coming soon. And the last

53:29

couple of slides: practical use of energy. So, you know the sort of almost no-brainer is that if you have charge

53:36

separation, that you ought to be able to capitalize on that to get energy. We've put electrodes in there.

53:43

Kurt Kung, if you want to speak to him, he's here, is working on this project. It looks quite promising to get electrical

53:50

energy out of this. This is from the Sun, energy from the Sun, using water, a renewable resource.

53:57

And finally: obtaining drinking water. If you have hydrophilic material and

54:03

you put contaminated water next to it, that is water that's got junk in it, bacteria, colloidal particles,

54:11

whatever, all the stuff gets excluded. And the exclusion zone is pretty big, this is EZ, and so if you could collect

54:18

this EZ water, that should be free of contaminants. We don't know for sure, but we think that

54:25

salt might be excluded too, and if salt is excluded, then it might be possible. We don't know this yet, to take ocean water

54:35

and get drinking water from the ocean water. And this would be using energy from the Sun, not doing reverse osmosis,

54:43

where the energy requirements are huge. So, the main conclusions. One is the phases of water. So, we know the three

54:51

phases and it looks as though the EZ phase is another phase of water. If you take account

55:00

of the fact that water has not three phases, but four phases, then you can begin to understand many phenomena,

55:07

including many everyday phenomena, a very small fraction of which I've been able to talk about. Another point is that a

55:15

glass of water is not at equilibrium with the environment. It's a transducer that takes energy in and

55:22

converts that to other kinds of energy. So, where we’ve come is starting with the idea that the water is absorbing this

55:32

kind of energy. I've suggested to you that this energy may be very important in various biological processes. We

55:40

have no clue yet. This is just at the beginning, to understand that water, or the radiant energy absorbed in

55:48

water, might play a very critical role in all of biology. In chemistry, well, if you read the chemistry books, anything that's

55:55

dissolved in water or suspended in water may have one ordered layer of water around it. And if what we

56:03

presented is right, it means that that paradigm is totally different. It means that basically what's in the chemistry

56:10

book in aqueous solution or suspension, may need radical reinterpretation. In terms of weather,

56:18

well, you know weather prediction is mostly based now on temperature and pressure. I think charge is much more important. I think to get better weather predictions, if you take account of the

56:32

charge in the clouds and the charge in the atmosphere, you have a much better chance to get a better prediction. In

56:39

terms of health, we were talking with various people about various kinds of water that contain energy. These kinds

56:46

of water have been demonstrated anecdotally, but in some cases more than anecdotally, to be able to reverse

56:53

pathologies of various sorts. And I think this is very promising for the future. In terms of food, if you want to store food,

56:59

prepare it, freeze it, you have to understand what water does. What happens during evaporation or freezing. I think

57:06

we have a better idea now. I've haven't demonstrated in detail, but we've demonstrated actually quite nice

57:15

filtration. You can remove the EZ and it's free of contaminants. And possibly desalination.

57:21

And getting energy from the water. So, I leave you with that and I think water has been really exciting to

57:31

[observe] and I think we've discovered some stuff that has some potential for the future. Thank you.

57:48

[Music]