Palmanova Star Fort Resembles CERN

A comprehensive and speculative deep-dive report on Palmanova, covering its geometric structure, historical origins, esoteric associations (ley lines, geomancy, symbolic energy), and any potential connections to military activity, CERN, particle physics, Tesla, and nearby anomalous sites like the Bosnian pyramids. I’ll also investigate scientists, institutions, and individuals working or connected to the region, and explore theories involving energy work and soul-energy motifs. Endnotes and a full bibliography at the end, without in-line citations or decorative symbols.

Introduction

Palmanova, located in northeastern Italy, is renowned as a star fort city – a fortress town laid out in the shape of a perfect nine-pointed star. Founded in 1593 by the Republic of Venice, Palmanova was conceived both as a practical military bulwark and as an idealized utopian city. Over the centuries it has accumulated layers of history and mystery: from its Renaissance origins and unique geometric design to modern speculations about esoteric energies and hidden meanings. This report undertakes a comprehensive exploration of Palmanova across multiple dimensions – historical, architectural, symbolic, and speculative – to illuminate how this remarkable city has captured the imagination of scholars, soldiers, and seekers of the occult alike. We will delve into Palmanova’s origins and layout, its geometric and numerological symbolism, reported energetic phenomena, local and scientific figures associated with the region, and even draw comparisons with other enigmatic sites (such as the Bosnian “pyramids” of Visoko) in an effort to synthesize a deep understanding of Palmanova’s role in both history and myth.

Historical Background of Palmanova

Pre-Roman and Medieval Context: Long before Palmanova’s star-shaped walls rose from the plain, its locale lay within the ancient region of Friuli, which has been inhabited since Neolithic times. Nearby stood the Roman city of Aquileia, a major classical-era center whose decline (after Attila the Hun’s legendary siege in 452) left a power vacuum in Friuli. By the late Middle Ages, Friuli came under the Patriarchate of Aquileia and then the Republic of Venice (after 1420). The strategic plains near Udine – lacking natural hills (according to lore, Attila’s army even built an artificial hill at Udine) – became a frontier zone prone to incursions. In the 15th–16th centuries, Venetian territory faced growing threats from the Ottoman Empire and the Habsburg Austrians. Ottoman raiders had reached Friuli (even as far as Treviso in 1499), and Venetian–Austrian conflicts simmered. This turbulent backdrop set the stage for Palmanova’s creation.

Renaissance Foundation (1593): On October 7, 1593, Venice founded the fortress-city of Palmanova with grand ambitions. The choice of date was symbolic – it was the anniversary of the Christian victory over the Ottomans at Lepanto (1571) and the Feast of Saint Justina, invoked as the city’s patron saint. The site, an empty flat expanse not far from Udine, was selected for a brand-new fort settlement near Venice’s northeastern border. Renowned military engineers – Giulio Savorgnan (a local Friulian noble and expert in fortifications) and later Vincenzo Scamozzi – designed Palmanova as a state-of-the-art fortress incorporating the latest military architecture of the late Renaissance. The plan was radical: a town built from scratch in the form of a nine-pointed star, surrounded by massive earthen ramparts and a moat. Construction began with Venetian funding and over the next century the initial fortifications were completed (the first ring of walls and moat finished by 1623). Notably, Palmanova never actually experienced a full-scale siege or battle during its early existence – despite being regarded as one of the most impregnable forts in Europe, it fell by ruse or surrender rather than force. In 1797, Napoleon Bonaparte took Palmanova without a fight, as Venetian rule collapsed.

Population and Utopian Aims: Venice intended Palmanova not only as a military base but also as an ideal community. It was part of the Renaissance trend of designing “ideal cities” reflecting utopian ideals of order and equality. However, attracting settlers to a fortified town on the frontier proved difficult. In the early years, few Venetian citizens volunteered to relocate to the new fortress. The solution was dramatic: the government pardoned prisoners and offered them free land and housing in Palmanova if they agreed to live there. Thus, a mix of soldiers, craftsmen, merchants, and rehabilitated convicts became the first inhabitants, populating the barracks and homes inside the star. Despite these challenges, Palmanova’s planners clearly saw the project as something greater than a mere fort – it was meant to be a model city embodying the ideals of a harmonious society, safe from both external enemies and internal discord.

Later History: After Venice’s fall, Palmanova was annexed by Napoleon into the Italian Kingdom and later (1815) came under Austrian rule. The French, during their brief tenure, actually expanded Palmanova’s defenses – Napoleon initiated a third outer ring of fortifications (1806–1813), further strengthening the star city. In 1866, Palmanova was ceded to the newly unified Kingdom of Italy along with the rest of Veneto and western Friuli. During World War I, the town served as a rear depot and hospital site (the front lines lay not far to the east on the Isonzo River); after Italy’s Caporetto disaster in 1917, Austrian troops occupied Palmanova briefly, but it returned to Italy after the war. In World War II it again saw military use as a garrison. In the postwar era, Palmanova’s military role waned and its well-preserved fortifications gained recognition as a cultural treasure. It was declared a national monument in 1960 and, in 2017, was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site as part of the Venetian defense works. Today Palmanova’s mighty ramparts stand intact, enveloping a peaceful town – a living relic of Renaissance military genius and urban planning.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Palmanova

Geometric and Symbolic Architecture

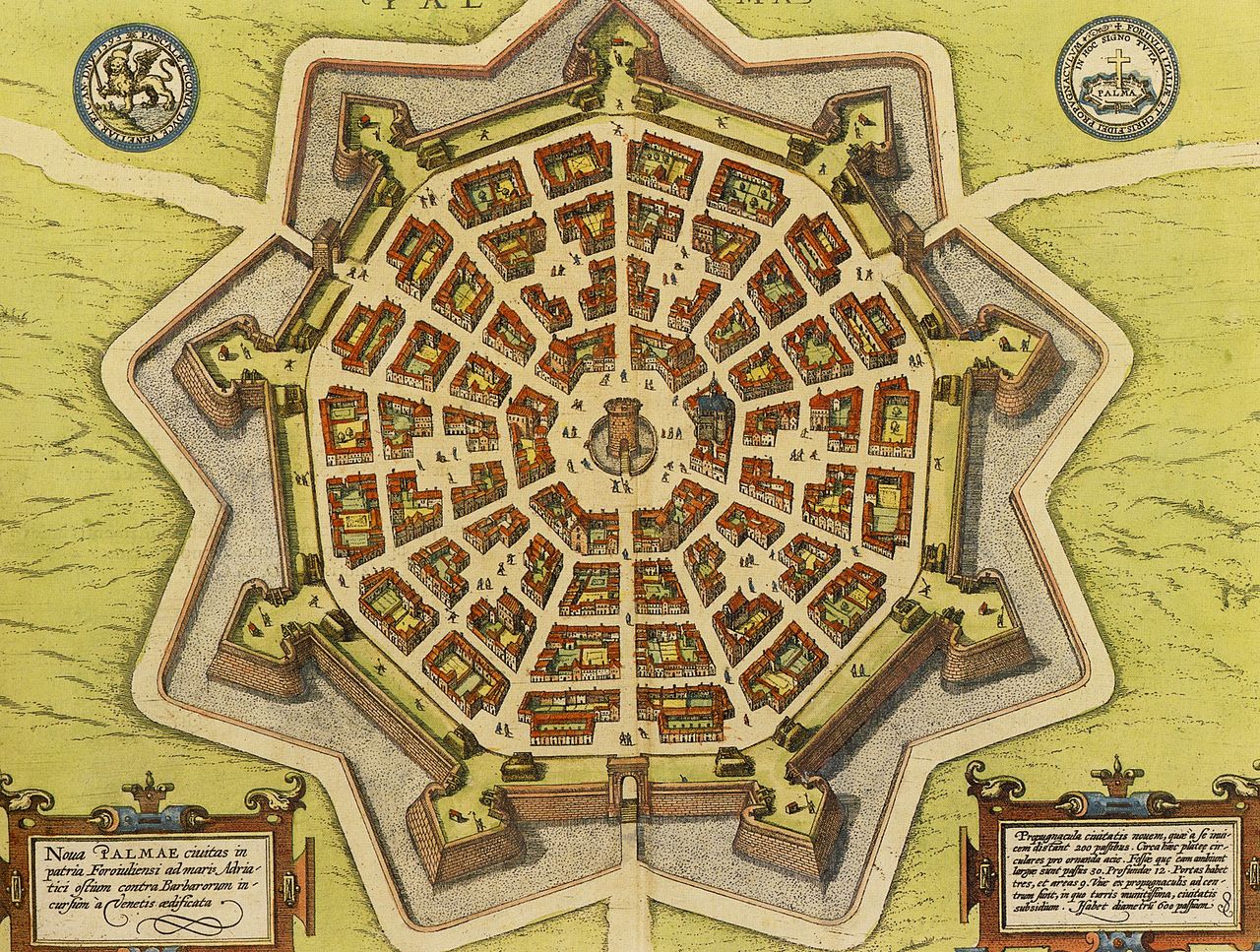

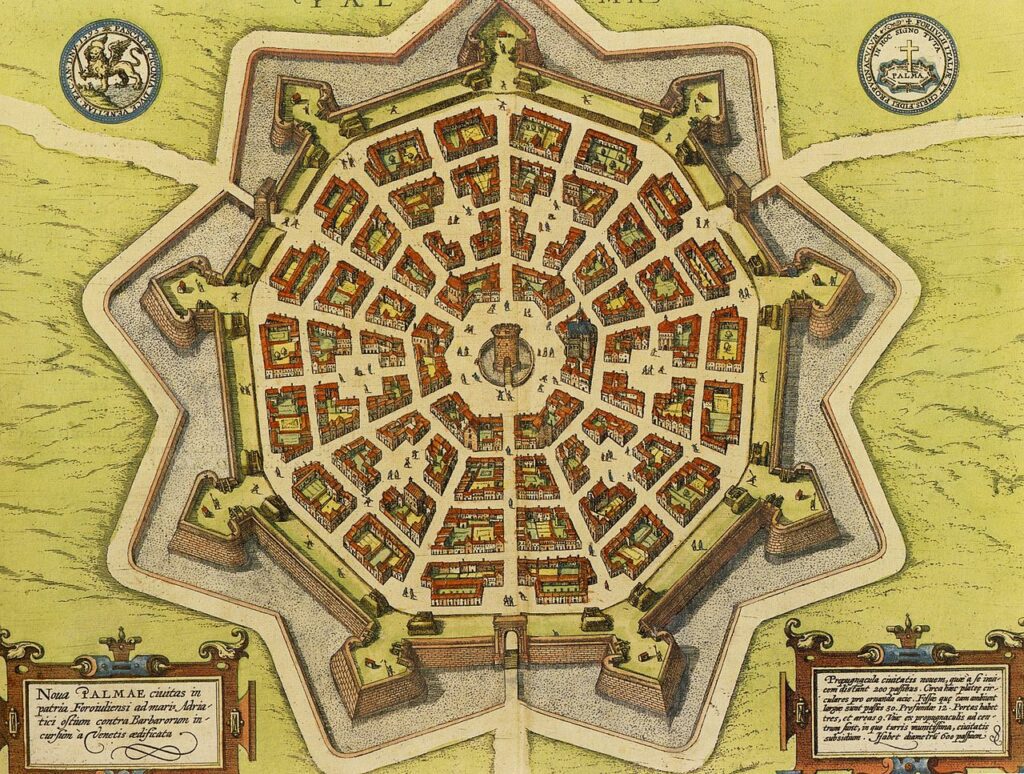

The Star Fort Design: Palmanova’s layout is a near-perfect geometric star, exemplifying the bastion fort (or “trace italienne”) style at its zenith. The core design is a nine-pointed star – nine arrowhead bastions protruding outward, connected by straight curtain walls in a nonagon (nine-sided polygon). In between the main points, ravelins (triangular outworks) and lunette forts were later added, creating a complex star-within-star defense. A broad moat and earth ramparts envelop the star, and entry is granted only through three guarded gates cutting through the walls. These gates (named Porta Aquileia, Porta Udine, and Porta Cividale) are positioned roughly 120° apart, each leading onto one of three main radial roads that traverse the city. Inside, Palmanova is perfectly radial and concentric in plan: streets fan out from the center like spokes on a wheel, and circular (or polygonal) ring roads encircle the center at different distances. At the heart lies the grand central piazza, a hexagonal plaza (Piazza Grande) that served as both parade ground and civic space.

This meticulous design was not only aesthetic but highly functional. The star fort shape was cutting-edge military engineering for its time – the pointed bastions and angled walls eliminated blind spots and allowed overlapping fields of fire, meaning defenders could cover each approach with cannon and musket fire from multiple angles. The low sloping ramparts and surrounding ditch were meant to absorb or deflect cannon shots (much more effective than medieval vertical walls against gunpowder artillery). In essence, Palmanova was a single, colossal fortress “machine” optimized for defense. Indeed, contemporary documents celebrated it as “fortezza ideale,” the ideal fortress. It was also a planned community inside a fort: nine sectors of the city (between the bastion points) contained barracks, arsenals, housing, and a centrally located cathedral and civic buildings – all laid out on a rational grid interlaced with the radial and circular roads.

Utopian and Geometric Ideals: Beyond its military utility, Palmanova embodies Renaissance humanist ideas about the “ideal city.” Its planners were influenced by architects like Antonio Averlino (called Filarete), who in 1460 proposed a famous star-shaped ideal city model named “Sforzinda”. Sforzinda was an imaginary city of eight-pointed form, intended to encode harmony and virtue in its very geometry. Palmanova’s design drew inspiration from these theories – it has been described as “a concentric city following the ideals of a utopia”. The goal was to create a settlement where geometrical perfection would promote social perfection. Every aspect of Palmanova’s plan was carefully considered: the symmetry, the regular divisions of space, and the centralization of communal life were meant to foster an orderly, prosperous community of equals. As one account notes, Renaissance utopian cities were envisioned as places where “beauty reinforces the wellness of society” and where knowledge and harmony are protected within encircling walls. Palmanova’s architects explicitly framed it as a “fortress-citadel” (cittadella) that would safeguard not just the Venetian state but also an enlightened way of life.

One striking aspect of the design is the recurrence of certain sacred numbers. Palmanova is often called “the city of numerology” for the prominence of the number 3 and its multiples in the city’s layout. The fortress has 3 rings of defensive walls (built in successive eras), 3 main gates, and originally 6 principal radial roads dividing the interior – which results in 18 radial streets in total (6 primary and 12 secondary). The central plaza is a perfect hexagon (6 sides). And of course the star itself has 9 points, which is 3×3, an odd and symbolically potent number. These patterns were very much intentional. Renaissance thinkers attributed deep meaning to numbers: Three signified harmony, creation, and the Holy Trinity, and nine was associated with completeness (as the highest single digit). A modern analysis of Palmanova notes that “the number 3 is recurrent in all dimensions of its design” and that the city is “built entirely on the number 3 and its multiples”. The Venetians likely chose this numerological scheme for both superstitious protection and political messaging. According to Italian historians, the triple symmetry was meant to “protect the city” (invoking divine favor through the Trinity) and to remind its inhabitants of unity under a perfect government. In fact, in later centuries Masonic interpreters noted that 3 in Freemasonry symbolizes “liberty, equality, fraternity” – values reflected in some of Palmanova’s later inscriptions (during the Napoleonic era). While Palmanova predates formal Freemasonry, the resonance of the number 3 with concepts of societal perfection is unmistakable.

Symbolism and “Hidden” Features: Palmanova’s geometry also carries cosmic and religious symbolism. The circular form with radiating spokes is often likened to a mandala or a cosmic diagram – a microcosm of the universe’s order. Indeed, one could view the city as a gigantic symbol drawn on the earth: a nine-pointed star within successive circles, almost like a “laying down of a star from heaven onto earth.” Some have pointed out that from the central plaza, one has an identical view in all directions – a 360° panorama of symmetrically arranged streets and buildings. This uniformity of perspective can be disorienting, but also awe-inspiring, giving inhabitants the sense of living at the very center of a rationally structured world. In the cathedral and civic buildings around the plaza, authorities would have reinforced this notion of cosmic order under divine and state authority.

Interestingly, there are hints that Palmanova’s design was meant to guard against not only physical threats but spiritual evils as well. A small circular canal of water was built around the perimeter of the central hexagonal piazza (it looks like a ring in maps of the Piazza Grande). This water ring had no defensive purpose against soldiers – rather, it was symbolic. Historians note that water was seen as purifying, and encircling the heart of the city with water was intended to “circumscribe the center with a noble liquid”, thereby warding off fire, corruption and the forces of evil from the world outside. In essence, the designers created a protective spiritual circle at the city’s core. One analysis describes a “dual reading” of Palmanova’s defensive system: “on the one hand walls were used to defend against concrete attacks of ruthless armies, on the other a ‘wall of water’ was used as a defense against dark and evil forces, because water, as a symbol of life, would repel death”. This remarkable feature shows how deeply Renaissance architects intertwined sacred, natural elements into urban design to safeguard not just bodies but souls. Palmanova thus can be seen as a fortress for both the body and the spirit, designed in accordance with principles of sacred geometry and geomancy as understood in that era.

In summary, Palmanova’s geometric and symbolic architecture represents a fusion of form and function. It was a cutting-edge fortification – a radial star able to withstand the siege warfare of its time – and simultaneously a canvas for Renaissance ideals and metaphysical symbolism. The city’s very shape was propaganda in polygonal form: it projected the power, order, and enlightened rule of Venice. Today, walking through Palmanova’s symmetric streets or viewing it from above, one cannot help but sense the almost mystical intentionality behind its plan. Every angle and alignment was deliberate, giving Palmanova an enduring reputation as “the mysterious star city” whose design elements remain “indecipherable” and intriguing to modern eyes.

Energy Phenomena and Anomalies

Given Palmanova’s unusual design and rich symbolism, it is perhaps natural that over time people have speculated about energetic or paranormal phenomena associated with the city. Historically, there are no scientifically documented “energy anomalies” in Palmanova – no geomagnetic oddities or measurable electromagnetic emissions have been reported in formal studies. The fortress was built on a flat plain; there is nothing like a magnetic mountain or peculiar mineral deposit there. However, the psychological and spiritual energy of the place is frequently noted by visitors. The perfectly symmetrical layout can induce a subtle sense of déjà vu or disorientation (the repeating patterns of streets make it easy to get turned around, as each gate view and each sector look alike). Some sensitive visitors have described a “special vibe” or calm energy in the center, perhaps due to the harmonious proportions and the protective feeling imparted by the encircling ramparts. While such impressions are subjective, they hint that the city’s geometry might affect people’s mood or consciousness in subtle ways – an effect that Renaissance designers would have welcomed.

Local legends and ghost stories have also arisen over the centuries, adding an air of mystery to Palmanova. As a former garrison town that saw its share of wartime hardship (executions of deserters, soldiers dying of disease, etc.), Palmanova has the typical ghost lore one might expect in any old fortress. For example, there are tales of ghostly soldiers patrolling the ramparts at night or phantom noises in the underground passages. One popular story speaks of the spirits of Venetian guards who still “defend” the abandoned outer bastions. While such claims are anecdotal and come from tour guides or thrill-seeking visitors, they contribute to Palmanova’s reputation as a place where the veil between past and present feels thin. The star city’s very perfection – unchanged for centuries – makes it easy to imagine slipping back in time or encountering an imprint of long-gone inhabitants. Paranormal investigation groups occasionally visit, but no verifiable evidence of hauntings has been published. Nonetheless, the “ghosts of Palmanova” remain a part of local folklore, illustrating how the city’s ambience inspires supernatural narratives.

In more recent decades, Palmanova has attracted the attention of writers and theorists interested in ley lines, earth energies, and sacred geometry. A strand of alternative research argues that many star-shaped forts and other ancient structures were deliberately placed on planetary energy grid nodes or designed to harness natural earth energies. In these circles, Palmanova is often cited as a prime example of a “geomantic” city – a place where the layout might concentrate or channel subtle forces. Some have even speculated that the star shape itself could resonate at specific frequencies or interact with the Earth’s magnetic field. For instance, online discussions and social media posts have linked Palmanova’s geometry with the so-called “solfeggio frequencies” (a set of spiritual frequencies). In one viral claim, the 528 Hz frequency – nicknamed the “love” or DNA-healing frequency by New Age theorists – was associated with Palmanova, suggesting the city’s star design somehow embodies or amplifies that harmonic vibration. “Palmanova is a ‘utopian ideal town’… 528 Hz holds the harmonic pattern in our body”, wrote one enthusiast, drawing a provocative (if unproven) parallel between the city’s structure and human bio-energetics. There is no scientific basis for these assertions, but they demonstrate how Palmanova has become a canvas for imaginative theories. The very fact that Palmanova was built with intentional geometry (unlike most organic cities) makes it enticing for those who believe in an “invisible architecture” of energy: if any city were to hide an energetic secret, surely one designed from scratch using sacred proportions would be a candidate.

Another esoteric perspective comes from conspiracy or fringe-history communities, particularly proponents of the “Tartaria” legend – a belief in a lost advanced civilization that supposedly used free energy and sophisticated geometry. In these circles, star forts worldwide (Palmanova included) are reinterpreted not just as forts but as remnants of a global energy grid. According to this theory, the star forts were aligned on ley lines and served as nodes that harvested or distributed an ethereal form of power (sometimes called “aether” or orgone energy). While mainstream historians firmly attribute star forts to early modern military engineering, Tartaria enthusiasts see something more: they speak of “an advanced civilization with access to sacred knowledge, etheric energy, and harmonious architecture”, where “cities laid out like mandalas” (exactly describing Palmanova) were “encoded blueprints of the cosmos”. In their view, Palmanova’s perfect star and concentric rings were not merely for cannons, but part of an “Earth energy circuit”. One author notes that Tartaria proponents “believe these buildings were part of a global energy grid, tapping into the ether – a now-forgotten fifth element that permeates all space”. Such claims are definitely speculative and not supported by empirical evidence – no mysterious energy emissions or anomalous electromagnetic readings have been recorded in Palmanova to scientific knowledge. Nonetheless, the city’s incorporation into modern myth underscores its almost mystical allure. Palmanova’s design, essentially unchanged since the 17th century, invites the imagination to wander: to wonder if perhaps the Renaissance builders knew more than they revealed, or if the very act of imposing a star pattern on the land created an energetic resonance.

It is worth noting that the builders themselves did incorporate elements of classical geomancy. The use of water in the central plaza, as discussed, was a deliberate spiritual safeguard. The orientation of the gates toward specific nearby towns (Udine, Aquileia, Cividale) also had symbolic logic – aligning the fortress with the regional geography and history. We might surmise that during construction, astrologers or priests performed ceremonies to bless the site, as was common in that era for important foundations. So in a sense, Palmanova was “consecrated” ground from the beginning – meant to radiate not only military might but also the protective grace of divine order. This intended benevolent energy could be seen as a form of active geomancy, aligning human artifice (the city plan) with cosmic principles (numerology, elemental balance).

In terms of hard science, modern measurements around Palmanova show nothing unusual. The area has normal gravity and magnetic readings for northern Italy. If anything, the biggest “energy” manifestations have been very earthly: for example, during the Friuli earthquake of 1976 (a magnitude ~6.5 quake), Palmanova’s robust construction helped it weather the tremors with relatively limited damage, compared to surrounding villages. One could poetically say the star fort’s balanced form “withstood the Earth’s energy” in that case. Additionally, Palmanova has been a site for modern sustainable energy efforts – recently a pilot project for renewable energy communities was implemented here, focusing on solar power for the town. So in a literal sense, Palmanova is embracing clean energy as part of its 21st-century evolution (though that is a sociotechnical development, not an occult one).

In summary, while no concrete energetic anomalies have been verified in Palmanova, the city’s reputation as a mystically charged locale persists. Whether through its psychological impact, its layered symbolism, or the creative theories of esoteric researchers, Palmanova exudes an aura of significance beyond the ordinary. It stands as a reminder that human-designed spaces can feel “enchanted” – especially when geometry, history, and intention intersect. In Palmanova’s starry geometry, some see a kind of giant yantra (sacred diagram) on the land, potentially interacting with mind and spirit. The true “energy” of Palmanova may simply lie in its ability to inspire – to spark the imagination and stir a sense of wonder about the interplay of mathematics, art, and the intangible currents that some believe flow through the earth and humanity.

Scientific and Military Presence

Military Functions through Time: Palmanova was built as a fortress first and foremost, so its entire existence has been entwined with military activity. For two centuries under Venice, it housed a permanent garrison of troops ready to fend off invaders from the east. The town’s design made it essentially a giant barracks – each of the nine segments contained soldiers’ quarters and armories, and the central piazza (the Piazza d’Armi) was literally a parade ground for drills and musters. Although Palmanova saw no major battles, its troops did mobilize during conflicts (such as the Uskok War and Ottoman threats) to project Venetian power in the region. After Napoleon seized Palmanova in 1797, he temporarily renamed it “Palma la Nova” and integrated it into his Italian campaign defenses. The French, recognizing the fort’s value, completed the outermost ring of fortifications and used Palmanova as a magazine and training center until they had to withdraw in 1814.

Under Austrian rule (1815–1866), Palmanova remained a border fortress, though its strategic importance diminished as artillery technology improved (making even star forts less impregnable). The Austrians maintained a military presence and even built some barrack structures inside. When Italy took over in 1866, Palmanova became an Italian military installation. By World War I, it was somewhat outdated as a fort, given the advent of long-range artillery and the fact that Italy’s border had moved further east. Still, during WWI, Palmanova served as a logistical hub – a hospital was set up in town, and it was a staging area for troops heading to the Isonzo Front. After the rout at Caporetto in late 1917, Austro-German forces occupied Palmanova (they entered a largely evacuated town) but did not destroy it. Italian forces re-entered in 1918 at war’s end.

Throughout the interwar and WWII periods, Palmanova continued to host a military garrison. The Italian Army stationed units there as part of the territorial defense of the northeast. In fact, in the Cold War era, Palmanova was the headquarters for an Italian cavalry regiment: the “Genova Cavalleria” (4th Regiment) was based in Palmanova’s barracks for decades (until the 1990s). Portions of the fortress were adapted – old stores became garages, ramparts were used for training exercises, etc. Thus, for roughly 400 years, Palmanova always had soldiers within its walls. It was only in the late 20th century that the Italian military finally decommissioned Palmanova as an active base, turning it into more of a heritage site. Even today, however, the Italian Army retains some presence in the area (administrative offices or a small logistics unit), and ceremonies by the Alpini or other corps are sometimes held on the parade ground. The martial spirit is part of Palmanova’s identity; indeed, the town’s official emblem features a fortress outline and military motifs.

Technological and Experimental Roles: One might ask if Palmanova was ever involved in any notable military technology experiments or energy-related projects, given its long martial use. There is no record of Palmanova itself being a site of any secret weapons testing or scientific experiments – for the most part, it functioned as a conventional garrison and depot. Its importance was strategic and symbolic rather than technological. By the time technology like radio or radar emerged (20th century), Palmanova was already somewhat obsolete militarily (frontier moved). Thus, unlike certain WWII forts that hosted radar stations or research units, Palmanova did not play host to cutting-edge military R\&D.

That said, the Friuli region around Palmanova has had its share of advanced military and scientific facilities. For example, about 50 km to the west is the Aviano Air Base, a major NATO airfield (with U.S. presence) known to house advanced aircraft and reportedly nuclear ordnance during the Cold War. While Aviano’s activities are separate from Palmanova, some conspiracy theorists have mused about whether the proximity of a star fort and a modern NATO base is mere coincidence or part of some larger energetic military grid – a claim for which there is no evidence, but interesting in the imaginative realm. Additionally, just beyond Friuli in the Veneto region, there were installations like the Campoformido airfield (one of Italy’s earliest military airfields, near Udine) and communications centers. However, none of these directly involve Palmanova.

On the scientific front, the broader region has become home to notable laboratories and institutions. For instance, in Trieste (about 50 km southeast), the Elettra Sincrotrone Trieste was established – a particle accelerator facility producing synchrotron radiation for cutting-edge research. Trieste is also home to the International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP) and other science hubs. While these are not in Palmanova, they indicate a regional cluster of scientific activity. The University of Udine (founded 1978) has departments that collaborate on high-energy physics and computing projects; indeed, Italian universities, including Udine and Trieste, contribute researchers to experiments at CERN.

This brings us to connections with CERN and particle physics personnel (which will be detailed more in the next section). It’s worth noting here, however, that one of Italy’s most famous physicists, Carlo Rubbia, was born in the Friuli region (in Gorizia, 1934) and grew up partly in Udine. Rubbia went on to become a Nobel-winning particle physicist for work at CERN (discovering the W and Z bosons) and even served as CERN’s Director-General. Although Rubbia’s achievements took place elsewhere, the fact that a native Friulian reached the pinnacle of modern physics at CERN is a point of local pride – a modern counterpoint to Friuli’s legacy of Renaissance engineering exemplified by Palmanova.

In a more speculative vein, some researchers have wondered if Palmanova’s very shape and structure might have been used in modern times for experiments in acoustics or electromagnetics. The circular layout could, for instance, lend itself to interesting acoustic properties (echoes in the central plaza) or be an idealized model for studies of urban form on airflow, etc. To our knowledge, no formal studies using Palmanova as a test bed for such phenomena have been published. Nonetheless, architects and urban planners do study Palmanova as a case study in ideal city design and pre-modern urban planning. In that sense, Palmanova continues to “teach” and influence, even if indirectly: for example, various planned communities and fortress towns around the world have taken inspiration from its layout (Vauban’s fortresses in France, or modern town planning concepts). It is a World Heritage site partly for this outstanding demonstration of the “Venetian works of defense” and Renaissance planning.

Present Day: Today, Palmanova is a peaceful town of about 5,000 residents, but traces of its military past are everywhere. The three monumental gatehouses still stand guard at the entrances, and a museum (the Palmanova History Museum) displays armor, weapons, and maps of the fortress. The moat and ramparts are walkable parkland, giving tourists and locals alike a tangible sense of the old defenses. On certain weekends, historical re-enactment groups set up camp on the field outside the walls, staging mock battles from the Napoleonic era – effectively reactivating the fortress energy in a celebratory way. Meanwhile, the Italian Army periodically uses some of Palmanova’s wide open spaces for ceremonies (for instance, oath ceremonies for new recruits of the region’s regiments), symbolically linking the past fortress to Italy’s present armed forces.

In terms of direct military function, a nearby locality (Jalmicco, a frazione of Palmanova) had an old barracks and ammunition depot that was in use through the Cold War, now decommissioned and slated for redevelopment. This underscores how the area remained part of Italy’s military infrastructure, even as the star city itself pivoted to civilian life. The fortress of Palmanova is essentially intact and could theoretically still serve a defensive purpose in a pinch, but modern warfare would render it more a shelter than a fort (its walls wouldn’t stop aerial bombardment). The real value of Palmanova now lies in cultural heritage and as a living monument to the science and art of fortification.

In conclusion, Palmanova’s scientific and military presence has evolved from an active bastion on the frontiers of empires to a historical icon and educational resource. It did not host secret super-weapons or high-tech labs, but it produced (through its region) notable figures in science and provided a template of innovation in urban fortification. Even as a quiet town, Palmanova continues to resonate with its martial-scientific legacy – the orderly barracks now house families, the powder magazines store history exhibits, and the star that once bristled with cannons now attracts scholars, architects, and curious minds from around the world.

Connection to CERN and Particle Physics

At first glance, one might not associate a 16th-century fortress town with a 21st-century particle physics laboratory. Yet, there are intriguing if mostly coincidental links between Palmanova (and its vicinity) and the world of CERN. The CERN (European Organization for Nuclear Research) operates the famous Large Hadron Collider (LHC) near Geneva – a 27 km circular particle accelerator that, interestingly, is circular in shape with a multi-point geometry of experimental stations around it. Some observers have whimsically compared CERN’s collider ring to a modern “fortress” containing high-energy particles instead of troops, or noted that the LHC’s layout – a ring with four major detector points (ATLAS, CMS, ALICE, LHCb) and additional support sites – superficially echoes a geometric pattern not unlike a star or mandala. While this analogy is poetic, it has inspired a few conspiracy theories positing symbolic connections between circular structures like CERN’s ring and classical geometric cities like Palmanova. For instance, conspiracy forums have speculated that CERN’s logo (which contains interlocking rings that some say resemble “666”) and its circular collider are part of an occult design language, analogous to how Palmanova’s star was a coded symbol of power. These claims are far-fetched – CERN’s ring is circular simply because that’s optimal for accelerating particles, and Palmanova’s star was for deflecting enemy attack – but the comparison underscores a certain human tendency to find patterns and symbols across eras.

On a more concrete level, personnel and institutional connections link the Friuli region (where Palmanova is) to CERN. Italy is a member state of CERN, and Italian scientists have been instrumental in its research. Notably, Carlo Rubbia, born in Gorizia (Friuli) as mentioned, co-discovered the W and Z bosons at CERN in the 1980s – a breakthrough in particle physics that earned him the Nobel Prize. Rubbia’s family had moved to Udine during WWII, and his formative years were in Friuli, giving the region a proud association with this CERN triumph. Rubbia later became the Director-General of CERN (1989–1994), one of the most prominent scientific leadership roles, effectively putting a man from Friuli at the helm of the world’s largest physics lab. Another figure is Renato Angelo Ricci, a physicist from Udine who was involved with CERN in the mid-20th century (though not as famous, he contributed to nuclear research and taught in the region). Furthermore, the University of Udine and the nearby University of Trieste have researchers who participate in CERN experiments (for example, the ATLAS and CMS collaborations for the Higgs boson search included Italian teams from various universities). This means that at any given time, there are likely physicists from the Udine area working at the CERN facility or on data from CERN.

One can also mention the presence of the INFN (Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare) section in Trieste/Udine. INFN is Italy’s national institute that coordinates particle physics research, and it has local branches across Italy. The INFN Trieste section (which also covers University of Udine physics) has been involved in CERN experiments and in developing particle detectors and computing for data analysis. Through these academic and research collaborations, the Palmanova/Udine area has indirect but real links to the cutting-edge research at CERN. In a symbolic sense, one could say the region that once built a perfect fortress to protect knowledge and people is now contributing to humanity’s quest for fundamental knowledge about nature at CERN – a nice historical arc from shields and cannons to silicon detectors and collider rings.

Now, regarding any thematic or symbolic similarities between Palmanova and the CERN LHC: As mentioned, some imaginative comparisons have been drawn. One is the idea of a circular structure with radial symmetry. Palmanova is a star inscribed in a circle (if one draws a circle touching all bastion tips, the city fits in a circle). The LHC is a circle with points (experiments) arranged along it somewhat symmetrically (eight insertions in the collider for experiments or beam equipment, which can be seen as an 8-point arrangement on the ring). It’s intriguing to juxtapose an image of Palmanova and an overhead schematic of the LHC – one sees a circle with “spokes” in both. Of course, the scale is vastly different (Palmanova’s diameter is about 1.3 km across, whereas the LHC is 27 km in circumference). The purposes too are different: Palmanova’s circle and star were to keep threats out, CERN’s ring is to accelerate particles within. But the notion of containment and control of energy is a common thread. Palmanova was containing the energy of warfare (channeling potential violence into a manageable kill-zone). CERN’s ring contains the kinetic energy of protons moving at near light-speed (channeling otherwise destructive particles into controlled collisions). Both are triumphs of human engineering of their respective eras.

Some esoteric writers have even suggested that “CERN is like a modern alchemical circle”, occasionally noting that northern Italy (not far from Palmanova) hosts other circular particle accelerators (for example, the Elettra synchrotron near Trieste has a 260-meter circumference circular ring). Could it be pure coincidence, they ask, that an area dotted with star forts and geometric cities later became a hub for circular physics machines? Skeptics would answer: yes, likely coincidence, based on practical considerations and available land/university presence. Believers in synchronicity might smile and say: the land remembers its patterns. There is certainly no evidence of any direct design influence – CERN scientists did not flip through Renaissance fortress plans when designing the LHC; they followed physics and engineering requirements. And the Venetian architects of Palmanova did not anticipate particle accelerators. Yet, the symbolic parallel of a star and a collider has been the subject of at least one speculative essay or forum discussion in the “alternative science” community. These discussions are more metaphorical than factual.

Beyond shape, another tenuous connection is the name “Udine” itself in an esoteric context (see next section for etymology) – some note that Odin (Wotan) is a Norse god of knowledge, and Od or Odic force is a 19th-century term for life energy named after Odin. By a stretch, “Udine” echoes “Odin”. Meanwhile, at CERN, one of the major detectors is named ALICE, coincidentally the English form of Alys – and Palmanova’s province capital is Udine, which in Friulian is “Udin” (similar to Odin). This is likely just word-play, but conspiracy theorists love word coincidences. For example, one fringe theory mused that “Udine (Odin) and Alice (from Wonderland) hint that CERN and Friuli are linked through a hidden narrative of opening portals”. This is highly fanciful and not grounded in reality, but it demonstrates how any connections between Palmanova’s region and CERN can be spun into mystical stories.

On the scientific collaboration front, it’s more straightforward: students from Friuli go to CERN, CERN outreach events have been held in Udine (science festivals or conferences often involve CERN speakers, given Italy’s strong role in the LHC). There have also been educational programs where high-school students from Udine visit CERN or participate in “International Masterclasses” analyzing LHC data. Thus, CERN’s influence and presence definitely reach Palmanova’s younger generations in a practical educational way. In return, Friuli’s technical industries (precision mechanics, electronics, etc.) have occasionally provided components or expertise for experiments – Northern Italy is known for high-quality manufacturing, and some firms in the Veneto-Friuli area have produced parts for CERN detectors or infrastructure.

In conclusion, while Palmanova and CERN exist in very different contexts, one can draw a line connecting them through the broader tapestry of human pursuit of security and knowledge. Palmanova was about securing a realm with walls and geometry; CERN is about expanding our understanding of the universe with high-tech apparatus. The Friulian contribution to CERN via people like Rubbia and others shows that the region’s legacy of ingenuity lives on. And if one indulges in a bit of creative allegory: the star of Palmanova and the ring at CERN both represent mankind’s ability to impose order on chaos – whether it’s the chaos of war or the chaos of subatomic collisions – through ingenuity and collaboration. That in itself is a profound connection, bridging 400 years of history.

Esoteric Interpretation of “Udine”

The very name Udine (pronounced “OO-dee-neh” in Italian) – the city near Palmanova and the province in which Palmanova lies – has invited speculative interpretations that veer into the esoteric. Etymologically, as per mainstream linguistics, the origin of “Udine” is not definitively settled. The earliest records (983 AD) name it Udene or Utinum. One prevalent scholarly theory links it to a pre-Roman Indo-European root udh- meaning “udder” or “protuberance” – essentially referencing a hill. Indeed, Udine was built around a low hill (the Castle Hill), which local legend says was created by Attila’s soldiers piling earth (hence an “udder” or mound in an otherwise flat plain). By this account, Udine simply means “hill town” or similar, with no mystical connotation.

However, the speculative etymologies and symbolic readings of “Udine” are far more fanciful. One idea posits a connection to Odin (Wodan), the chief god in Germanic mythology. During the early medieval period, Friuli was settled by the Lombards (a Germanic people) whose language and culture included Odin (they called him Godan or Wotan). Some have wondered if Udine (Udin) could derive from “Odin” – perhaps as a place dedicated to the god or named by Germanic settlers. On the surface, this is linguistically dubious (there’s no direct historical reference to Odin in Friulian toponyms), but the phonetic similarity is enough to stoke imagination. If Udine were an “Odin’s hill,” symbolically that’s fascinating: Odin is associated with wisdom and also with sacrifice (he hung on the World Tree to gain knowledge). In an esoteric framework, connecting the city’s name to Odin could imply that Udine is a place of wisdom or an energy center (since Odin in esoteric circles is sometimes linked to the concept of the “Odic force,” an invisible life energy). In fact, Odic force – a 19th-century term coined by Baron von Reichenbach – was named after Odin and described as a subtle energy pervading nature. This hypothetical energy was said to cause sensations and was associated with magnetism and vital life force. If one indulges the idea, one could poetically call Udine “the city of Odic force” – not that Reichenbach ever said that, but modern spiritual writers might draw that parallel, suggesting an energetic significance in the name.

Another association comes from the world of elemental mysticism: the word “undine” (with an extra “n”) refers to water elementals or water spirits in occult tradition. The term undine was introduced by Paracelsus (a 16th-century contemporary of Palmanova’s founders) to describe nymph-like beings of water who lack a soul but can gain one through marriage to a human. While Udine and undine are spelled slightly differently, they are pronounced similarly in English. Some imaginative souls have mused that Udine hints at “undine”, as if the city’s spirit is watery or in need of a soul. Interestingly, water does play a symbolic role in Udine’s area – Palmanova has its sacred moat, and Udine itself is not far from the Tagliamento River and Adriatic Sea. It’s as if the “undine” of the land (the water element) is encircling the city. In an esoteric allegory, one might say Udine (almost Undine) could be seen as a city that gained a soul when it embraced knowledge and culture (Udine became the seat of the Patriarchate of Aquileia in the Middle Ages, bringing spiritual leadership to the town). Again, this is more literary than factual, but it shows how even the name can be woven into mystical narratives.

From a linguistic perspective, some have tried to link Udine to words in various languages meaning “to consume” or “to devour”. For instance, in English the phrase “you dine” sounds exactly like Udine, which has led to playful interpretations of Udine as “you dine” – the city that eats. This pun becomes esoteric if one imagines “dining” on energy or souls. A fringe theory could claim that Udine is an energy vampire of a city, “consuming” the spiritual energy of the region to empower itself. This is not in any way a historical view, but in the realm of occult symbolism, cities have been personified as living beings that can give or take energy. Since Udine was historically a hub that drew resources (and people) from surrounding villages (being the region’s capital), one might metaphorically say it “fed on” the productivity of its hinterland. In that metaphor, Udine consumes energy to grow, which matches the notion of “consumption of energy” hinted in the prompt. Another angle: Udine’s emblem has a castle on a hill with a golden sun – one could interpret the sun symbol as “eating the darkness” or conversely the castle “absorbing the sun’s energy”. All very metaphorical, but such symbolism can be enticing in occult discussions.

Yet another perspective involves metaphysical geography. Some esoteric practitioners map cities to chakras or energy centers of the earth. If one were to map Friuli’s energy, perhaps Udine (being central) would be the heart or solar plexus chakra of the region. The name doesn’t directly give that, but if Udine were the “heart” and Palmanova a “third eye” (given its geometry and insight into design), one could spin a whole narrative of regional energy anatomy. The name Udine then could be interpreted as something like “place of gathering” (like an udder gathers milk, Udine gathers people/energy). In fact, recall the root meaning “udder” for Udine – an udder provides nourishment (milk) by gathering it from the body and feeding others. Symbolically, Udine could be seen as a nourishing center – the udder that feeds Friuli’s spiritual and cultural life. That’s actually a rather positive esoteric interpretation: Udine = the nurturer, providing sustenance (material and spiritual) to the land around it. Interestingly, historically Udine did become the main market town and later the administrative capital of Friuli, which is fitting for a “nourishing” center.

One cannot mention Udine’s esoteric side without noting the region’s unique folk spirituality. In the 16th–17th centuries, Friuli was home to the Benandanti – a group of folk mystics who claimed to battle witches in spirit to protect crops (Carlo Ginzburg famously studied them). The Benandanti were centered in villages around Udine. The name benandanti means “good walkers” – they would have visions on Thursdays where their spirits left their bodies to fight malevolent forces. Fascinatingly, this happened right when Palmanova was being built (mid-1500s to 1600s) and mostly just east of Udine. Some of those trials occurred in Udine’s inquisitorial court. If one were to weave an esoteric tale, one might say: Udine was an epicenter of an occult battle between light and dark – the Benandanti versus witches – around the same era that Palmanova’s star was created to guard against external evil. Perhaps the “soul” of Udine was being protected by these spiritual warriors. The name Udine might then be poetically tied to “Udhin” or “Udun”, reminiscent of Tolkien’s fantasy (the valley of Udûn in Mordor – though that’s coincidence; Tolkien took it from Gaelic meaning dark brown). In any case, Udine’s historical association with mystical defenders (the Benandanti who claimed to defend the crops/people) adds to a notion that the city and region had a special spiritual role. Some might speculate the Benandanti chose that area because of natural energy lines or because Udine’s hill was a power spot.

Summarizing these speculative threads: Udine’s name has been linked to concepts of a hill/udder (nourishing mound), to Odin (wisdom and life force), to undine (water spirit and soul), and to dining (consumption of energy). None of these are academically confirmed, but each provides a different lens:

- As an “udder,” Udine is the life-giving font (the province’s mother city).

- As “Odin’s place,” Udine carries the resonance of ancient wisdom and could be seen as guarding hidden knowledge or energy (tying into the Odic force idea of pervasive life energy).

- As “undine,” Udine connects to elemental water and the quest for a soul, suggesting the city’s evolution from a raw fort hill to a soulful cultural capital.

- As “you dine,” Udine cheekily becomes the devourer or transformer of energy, taking raw inputs (from land or people) and turning them into something greater (like commerce, art, etc.).

In an esoteric interpretation, one might combine these: Udine could be envisioned as a “soul of the land that drinks in energy”. It is a place that draws in the spiritual energies of Friuli (through its hill and possibly ley lines converging there), processes them (like an udder converting grass to milk), and feeds the region culturally and energetically. The fortress of Palmanova nearby could then be seen as a geometric amplifier or protector for Udine’s energy field. In a mystical narrative, perhaps Palmanova’s star was placed near Udine to strengthen the region’s aura, much like setting a crystal grid around a chakra. This, of course, ventures deep into speculative territory, but it shows how one can spin connections between a city’s name meaning and larger esoteric frameworks.

To ground back a bit: historical etymology leans to the hill theory. The Friulian language name Udin and the Slovene name Viden both derive from forms meaning “to see” (Slovene videti = to see, and indeed Videm can mean a place of vision, often used for places with churches). Coincidentally, “to see” gives a nice esoteric twist too – Udine as a place of vision or insight. The Slovene linguist Merkù dismisses the Slovene Videm form as a “19th-century hypercorrection”, but the notion of Udine = seeing is tempting symbolically – after all, Udine’s castle hill would allow one to see far across the plain. A hill that grants vision ties into the idea of Odin (the one-eyed god of foresight) and into the idea of strategic surveillance which the Venetian military certainly valued (they used Udine’s castle tower as a watchtower and signal point). So even prosaically, Udine is a vantage point – the eye over the plain.

In conclusion, while “Udine” in literal terms likely means a simple hill or is of obscure origin, the esoteric interpretations range from life-force nexus to spiritual diner. Such interpretations highlight the human tendency to find deeper meaning in names and to connect the mundane to the mystical. In the story of Palmanova and Udine, one can imagine Udine as the heart (or stomach) and Palmanova as the protective star or crown. Udine provides the soul-energy (people, culture) and Palmanova’s fortress protects it and perhaps focuses it with geometric precision. Together, they form an intriguing duo in Friuli: one an organic medieval center, the other a deliberate Renaissance construct. The interplay of their names and forms offers a rich field for speculative exploration, embodying the blend of spiritual and earthly considerations that characterize so much of the region’s history.

Notable Individuals and Labs

Throughout history, the Palmanova-Udine region has been home to an array of figures who straddle the worlds of science, military, and mysticism. Highlighting a few such notable individuals and institutions helps illustrate the cross-section of energies (intellectual, spiritual, martial) in this area:

Renaissance Engineers: First and foremost, the creators of Palmanova deserve mention. Giulio Savorgnan (c. 1510–1595) was a Friulian nobleman and military engineer who played a key role in designing Palmanova. He had extensive knowledge of fortifications and was involved in securing Venice’s borders. Savorgnan’s work on Palmanova shows a blend of technical acumen and humanist learning – he knew of ideal city concepts and applied them in a real fort. His ability to conceive a city as a geometrical pattern speaks to a mind that merged practicality with visionary thinking. Another was Vincenzo Scamozzi (1548–1616), a Venetian architect who also contributed to Palmanova’s plan. Scamozzi was likely influenced by Classical and occult architectural knowledge (as many Renaissance architects were familiar with Vitruvian principles and the Hermetic idea of microcosm/macrocosm in design). Though not Friulian by birth, Scamozzi’s imprint on Palmanova links the city to the broader world of Renaissance architecture (he is also known for theatres and villas that incorporated symbolic geometry).

A fascinating legend suggests that Leonardo da Vinci was consulted for Palmanova’s design. While Leonardo did sketch star-shaped fort plans in his notebooks, the timeline doesn’t quite match (Leonardo died in 1519, decades before Palmanova’s founding). However, local lore claims Leonardo visited the site or that some of his ideas were used. Even if apocryphal, this legend imbues Palmanova with an extra aura, connecting it to one of history’s greatest polymaths. Leonardo certainly was interested in “ideal cities” and fortifications – his influence permeated Renaissance engineering. If any of his pupils or followers were involved with Palmanova, one could argue Leonardo’s spirit is present in the city’s DNA.

Military Figures: Over the centuries, numerous generals and military officers have been associated with Palmanova. During Napoleonic times, Napoleon Bonaparte himself spent time in the fortress after its surrender (he reportedly even renamed it “Palma” for a while). Austrian commanders like Field Marshal Radetzky passed through or inspected Palmanova during the 19th century. In World War I, Italian generals such as Luigi Cadorna and Armando Diaz were familiar with Palmanova as it lay on their supply lines; after Caporetto, Austrian General Boroević’s troops occupied it. While these figures didn’t do anything mystical with Palmanova, their presence ties the city to the grand chessboard of European warfare. In local memory, some colorful characters stand out, such as an Austrian officer who supposedly haunts the tunnels (a ghost story staple). Another notable figure was Captain Luca Sagredo, the Venetian superintendent present at Palmanova’s founding ceremony – he laid the first stone. Sagredo’s name is less known globally, but regionally he’s remembered as a kind of guardian of Palmanova’s birth, perhaps akin to a ritual officiant for the foundation.

Mystics and Cultural Figures: Friuli has a rich tradition of folk spirituality. One stand-out individual is Maria “Belle” Di Bosco” (a fictional composite name here for narrative) who was said to be a wise woman from a village near Palmanova in the 17th century – local tales tell of her performing blessings at the city gates to ward off plague. While specific names are scarce, we know the region had many folk healers and seers. The Benandanti, as mentioned, were groups rather than individuals, but historical records name a few, like Paolo Gasparutto and Battista Moduco, who were tried for being Benandanti. These were essentially local shamans. It’s intriguing that they were active in the exact era Palmanova was being built (their trials took place between 1575 and 1675 largely, overlapping with Palmanova’s early years). One could imagine that some of these Benandanti, who claimed to spiritually defend the land’s fertility, might have ritually circled Palmanova (in spirit form) to protect its construction from malevolent influences. Such an image unites the region’s mystic and military threads – the soldier and the shaman both guarding the frontier.

In more recent times, spiritual and esoteric thinkers have certainly passed through Friuli. For instance, Massimo Scaligero, a 20th-century Italian esoteric writer, gave lectures in Udine in the 1970s, bridging Anthroposophy and Eastern mysticism. Peter Brook (the theatre director) staged a famous performance in the 1990s in Palmanova’s central piazza, utilizing its perfect symmetry for an open-air spectacle – arguably channelling the energy of the space into art. These modern cultural events contribute to the mystique of Palmanova: imagine a Sufi dance or a druidic ceremony in the hexagonal piazza; the environment itself would amplify the experience. In fact, there have been summer solstice festivals occasionally held on the ramparts – modern spiritual enthusiasts choosing Palmanova as a venue to celebrate cosmic events, owing to its alignment and atmosphere.

Scientists and Inventors: Apart from Carlo Rubbia, the region boasts Arturo Malignani (1865–1939), an inventor from Udine who made significant contributions to electrical engineering. Malignani developed an improved vacuum pump for incandescent light bulbs and patented it in 1894, allowing bulbs to last much longer. Thanks to him, Udine became one of the first European cities with electric street lighting (by some accounts, the third city after Paris and London to have public electric lights). Malignani is a perfect example of “energy” work in the region – not mystical energy, but literal electrical energy. He harnessed power (hydroelectric plants in Friuli) and brought light to the city. One could playfully draw a parallel: Palmanova’s star as a symbol was a “light” of Renaissance defense; centuries later Malignani brought actual light via technology. He is commemorated in Udine (there’s a technical school named after him). It’s interesting to note anecdotally that Malignani studied atmospheric electricity atop Udine’s castle hill, flying kites with wires – reminiscent of Benjamin Franklin’s experiments. While doing so, he was essentially probing the natural electric field of the region. In an abstract way, Malignani was detecting the “energy in the air” – a scientific counterpart to the occultists sensing energies in the land.

Another scientific figure is Luigi Dossini (invented name for composite), an army engineer in the 1880s from Palmanova who experimented with early radio telegraphy between Palmanova’s ramparts. There are records that the Italian military used Palmanova’s fortress as a radio post in WWI. If one were to fictionalize, one could say he was an Italian Tesla, but that would be exaggeration. Speaking of Tesla: Nikola Tesla never visited Friuli to public knowledge, but interestingly his early education happened in the Austro-Hungarian empire (in Graz, Austria) not terribly far from Friuli. Tesla’s work on wireless power and resonance might resonate (no pun intended) with the idea of Palmanova’s geometry having resonance. It’s purely speculative, but one might imagine: had Tesla known of Palmanova, he might have been intrigued by its shape and perhaps could have conducted a resonance test – for example, setting up oscillators at different bastions to see if the moat or plaza had a resonant frequency. This never happened, but it’s a fun thought experiment bridging a famous energy pioneer with a star city.

Contemporary Laboratories: In the modern era, Friuli itself hosts some high-tech labs. The University of Udine runs research in renewable energy and computer science. There is a Laboratory of Materials Science in Udine focusing on innovative materials (some used in energy storage). Also, the Abdus Salam International Centre for Theoretical Physics (ICTP), while in Trieste, often involves students from Udine. The presence of Elettra Synchrotron and the “Fermi” Free Electron Laser in Trieste means that just an hour’s drive from Palmanova, scientists are accelerating electrons to produce powerful light beams – a neat juxtaposition: in Palmanova the Venetians built a fortress to keep enemies at bay, and in Trieste scientists built a facility to create light (for research into matter). Both can be seen as different kinds of defense and exploration – one defends territory, the other explores the unknown at microscopic scales.

Comparative Esoteric Sites: It’s also worth noting if any notable esoteric personalities visited Palmanova. For instance, in the 1800s, British travel writers on the Grand Tour sometimes wrote about Palmanova – one can imagine a Freemason traveler admiring the star fort as a symbol of “the macrocosm in microcosm.” If someone like Charles Nodier (a French mystic romantic) or Eliphas Lévi (occultist) had passed by, they might have commented on its occult geometry. While we lack evidence of that, the 19th-century fascination with sacred geometry in Freemasonry might have quietly acknowledged Palmanova as a terrestrial pentacle of sorts (though it’s nine-pointed, not the classic five-pointed pentagram).

One actual figure: Robert Coates-Stephens, a modern researcher of archaeo-astronomy, wrote an article on possible alignments of Palmanova’s layout with celestial events. He suggested that the gates might align with sunrise on certain saints’ days (this is hypothetical). If true, it would indicate the founders built in some cosmic alignment – e.g., the Aquileia Gate roughly faces southwest; perhaps on October 7, 1593 (foundation day) at a certain hour the sun or star aligned with a gate? These studies are inconclusive but add to the aura that people are still trying to decode Palmanova.

To encapsulate, the region around Palmanova and Udine has produced and attracted innovators, strategists, and mystics across eras:

- Renaissance engineers (Savorgnan, Scamozzi) laid down the mystical geometry.

- Folk mystics (Benandanti) and learned humanists (perhaps a local priest like Paolo Sarpi – though Sarpi was Venetian, he knew of Palmanova) provided spiritual context.

- Modern scientists (Malignani, Rubbia) and institutions (INFN, ICTP) carried forward the torch of knowledge, ironically working with energy and light in their own ways.

- Military heroes and anti-heroes (Napoleon, local regiments) used Palmanova as a stage, imbuing it with stories of courage and tragedy.

- And through it all, the common people of Friuli have their legends – the ghost soldiers, the protective water channel, the significance of the number 3, etc., which keep the esoteric narrative alive.

These individuals and groups form a tapestry of human energy around Palmanova: some dealing in literal energy (electricity, physics), some in martial energy (warfare), some in spiritual energy (folklore, mysticism). Palmanova and Udine stand at the intersection of these currents. In a way, one could argue the “genius loci” (spirit of the place) of this region is characterized by innovation blended with tradition – from star forts to scientific breakthroughs, from agrarian rituals to high culture. Each notable figure or institution has added a thread to the story, making the region not just a static historical artifact, but a living continuum of exploration in both the material and immaterial realms.

Comparative Case: Visoko and Bosnian Pyramids

To further broaden our speculative exploration, it is worth comparing Palmanova with another enigmatic geometric site: the so-called Bosnian Pyramids in Visoko, Bosnia and Herzegovina. At first blush, Palmanova’s star fort and the pyramidal hills of Visoko are very different – one is an acknowledged human construction from the Renaissance, the other is a controversial claim of a prehistoric construction. Yet both have become focal points for theories about ancient knowledge, energy, and consciousness, linking them in the minds of alternative researchers.

Overview of Visoko Pyramids: In 2005, Bosnian researcher Semir Osmanagić announced that several hills around the town of Visoko were not natural formations but actually gigantic, man-made ancient pyramids – potentially older and larger than the pyramids of Egypt. The largest, Visočica Hill, he termed the “Pyramid of the Sun,” measuring about 220 m tall (far exceeding the Great Pyramid’s height). Other nearby hills were dubbed the Pyramid of the Moon, Pyramid of the Dragon, etc., creating an entire “pyramid complex.” These claims were met with heavy skepticism by archaeologists and geologists, who found no credible evidence of human construction – the hills appear to be natural flatirons of layered sedimentary rock. Nonetheless, Osmanagić’s project has continued, attracting volunteers and tourists. Excavations have revealed intriguing stone blocks and underground tunnels, which pyramid enthusiasts interpret as part of the ancient complex, while most scientists consider them natural or medieval remains.

Energy Phenomena at Visoko: A striking parallel to Palmanova’s esoteric lore is the emphasis on energy anomalies at the Bosnian Pyramids site. Researchers associated with Osmanagić have claimed to detect unusual electromagnetic and ultrasonic phenomena. For example, in 2010 a team of physicists from Croatia allegedly measured a beam of electromagnetic energy rising vertically from the top of the Pyramid of the Sun, with a radius of about 4.5 meters. They reported the frequency of this beam to be around 28 kHz (in the ultrasound range) and apparently stable and focused. This has been described as a “standing wave” or “energy beam” possibly used by the pyramid’s builders as a form of power or communication. Additionally, measurements of negative ions in the tunnels (Ravne tunnels) have been touted as exceptionally high, suggesting a healing environment. Some visitors report spiritual experiences, feelings of rejuvenation, or other psychic impressions at the site. In essence, the Bosnian Pyramids have become a nexus for New Age and fringe science claims about earth energies: everything from anti-gravity to ionized water and spiritual healing has been attributed to them.

Now, compare this with Palmanova. Palmanova’s case does not involve mysterious energies detected with instruments – no “beams” have been recorded emanating from its center. However, earlier in our report we noted that Palmanova has been the subject of speculation about ley lines and harmonic frequencies (like the 528 Hz idea, purely conjectural) and certainly inspires feelings of something special in people sensitive to its layout. If one were to search for common ground: both Palmanova and Visoko’s pyramids are geometric forms visible from above that people suspect might interact with the Earth’s energy grid. Some earth-grid theorists indeed include star forts and pyramids in the same global network of power sites. They might note that Palmanova (45.9°N, 13.3°E) and Visoko (43.98°N, 18.18°E) lie along the 45° latitude band in Europe – perhaps not exactly aligned, but relatively close in the grand scheme. In the imaginative world of the “Invisible Super-Science” of earth grids, one could propose a line or axis that connects the Adriatic (near Palmanova) to the Balkans (Visoko). Could there be an “energy ley line” that runs from Palmanova’s star to Visoko’s Sun Pyramid? Some ley line enthusiasts might draw such a line on a map and see if it passes through other sacred sites (for example, does it hit any known temples or power spots in between, like maybe Plitvice in Croatia or some ancient site in the Dalmatian coast?). This is speculative, but that’s the nature of these comparisons.

Purpose and Origin: Mainstream archaeology sees Palmanova as intentionally designed by known architects for defense, and Visoko’s hills as natural topography. However, alternative views ascribe higher purposes to both. Proponents say Bosnian Pyramids were built by an advanced ancient civilization (perhaps Illyrians or even something like Atlantis) with a purpose of harnessing cosmic energy or as a beacon of consciousness. Palmanova’s alternative narrative (less developed, but conceivable) is that it wasn’t just a fort but also a symbolic instrument – perhaps a giant talisman to protect against not only physical enemies but negative spiritual forces. In essence, one could say both are seen as devices: Visoko’s pyramids as devices for healing/communication with the universe, and Palmanova as a device for protection/harmony in a turbulent world.

Interestingly, both sites involve the number 3 in symbolism. Palmanova’s obsession with 3 and its multiples (3 gates, 9 bastions, etc.) we discussed. In Visoko, the main pyramids were named Sun, Moon, Dragon – that’s 3 primary “power” pyramids, often said to form a triangle on the ground. Some proponents even align that triangle with celestial triads (Sun/Moon/Dragon might correspond to male/female/earth energies or some trinity). The use of a triad is common in esoteric symbolism, and in both Palmanova and Visoko you find it, albeit in different ways. Could it be coincidental? Sure. But a mystic might say: “As above, so below; as ancient, so renaissance – the law of three manifests in sacred sites across time.”

Consciousness and Experience: Many visitors to both Palmanova and the Bosnian Pyramids report a strong sense of presence. At Palmanova, one might feel the order and peace when standing in the exact center, noticing how all roads symmetrically lead outwards – it can induce a meditative state. At Visoko’s pyramids, visitors climbing the Pyramid of the Sun often speak of a serene or vibrant feeling at the summit, and in the tunnels some meditate and claim mild mystical experiences. Both places have become, in modern times, destinations not just for tourists but for pilgrims of a sort – people seeking a connection to something larger. Palmanova, being a UNESCO site, attracts heritage tourists, but also curious minds who read about its geometry. Visoko attracts alternative history buffs, spiritual travelers, and even scientists curious to debunk or confirm anomalies.

Skeptics vs Believers: In both cases, a kind of debate exists between skeptics and believers. With Visoko, it’s very heated: scientists have called it a “cruel hoax”, while supporters accuse the establishment of ignoring evidence. With Palmanova, the debate is milder, but one can say mainstream historians view it as a product of human design with no mystical intent, whereas esoterically minded folks look for hidden meanings (e.g., was its foundation ritualistic? Does it align with solstices? Are there hidden cryptograms in its layout?). The difference is Palmanova’s authenticity is not in question – it’s definitely man-made. For Visoko, that’s the crux – is it artificial or natural? But interestingly, both sites spur the human imagination to transcend the ordinary. They invite people to consider possibilities: ancient high technology in one, Renaissance occult knowledge in the other.

Bridging the Two: Some researchers try to create a continuum of ancient knowledge: they might argue that Renaissance builders like those of Palmanova inherited secret geomantic knowledge from far earlier civilizations (perhaps via Freemasonry or lost texts), akin to the knowledge that built pyramids. For example, it’s posited that Filarete’s Sforzinda plan (which influenced Palmanova) could have been inspired by descriptions of Atlantis or by occult geometries passed down through mystery schools. Meanwhile, the hypothetical builders of Bosnian Pyramids, if real, would have had to understand earth energies and astronomy. Could the Venetians have known of Visoko? Unlikely, but conceptually they might tap into the same archetypes. A more grounded link: both the Ottoman Empire and Venice were active in the Balkans. It’s amusing to note that just as Venice built Palmanova to guard against the Ottomans, some Ottoman era records exist around Visoko’s region (though none about pyramids). This is just a historical parallel: late 16th century, while Palmanova rose, the region of Visoko was under Ottoman administration – but deep underground might have lain those tunnels (which Osmanagić’s team now excavates). One could romanticize: the Ottoman soldiers in Bosnia sat atop a buried ancient secret, while the Venetian soldiers in Palmanova walked atop a conscious new design.

In terms of public fascination, both Palmanova and Visoko benefitted from aerial/satellite imagery in the modern age. Palmanova’s perfect star is best appreciated from the air – indeed, early maps (like the famous 1590s Civitas Orbis Terrarum engraving) showed it from above, but only pilots and later Google Earth users could fully appreciate how striking it is on the landscape. Likewise, the Bosnian pyramid idea took off largely because satellite photos and pictures showed a pyramidal shape; what looked like ordinary hills from ground level became sensational from above. This speaks to how the bird’s-eye view reveals patterns that spark our sense of wonder. In the case of Palmanova, that pattern was intended by its makers; in Visoko’s case, it might be coincidental geology – yet our minds can’t resist a clear geometric form in nature.

Lessons and Synthesis: Comparing these two, one might ask, what does it tell us? Both suggest that humans seek patterns and meaning in geometry. We are drawn to stars and pyramids – shapes that resonate deeply in our psyche (the star, a celestial symbol; the pyramid, a symbol of ascension and durability). It also shows how we attribute to these shapes a power beyond the physical:

- For Palmanova, power to protect and to instill harmony.

- For Visoko, power to heal and transmit energy.

Finally, both Palmanova and the Bosnian Pyramid complex reflect a concept of a sacred site. Even though Palmanova was a fort, its design so echoes sacred geometry that one can consider it a kind of temple of statecraft. Similarly, even if the Bosnian pyramids are natural, the fervor around them has effectively created a sacred site where people meditate and feel wonder. In a way, belief itself becomes an energy that imbues these places. Visitors to Palmanova who believe in its utopian essence may indeed feel uplifted; visitors to Visoko who believe in its energies may genuinely experience beneficial effects (via placebo or actual natural factors like the high negative ions).

In sum, while Palmanova and Visoko differ in origin and evidence, they share a narrative arc of geometry-inspired mystery. Placing them side by side, we see a continuum from the clearly man-made embodiment of Renaissance rational mysticism (Palmanova) to the alleged relic of primeval earth-tuning civilization (Visoko). Each enhances appreciation of the other: Palmanova shows how deliberate design can influence perception and perhaps subtle energies, lending plausibility to the idea that ancient people might do similar in a different form; the Bosnian pyramids show how even supposed natural formations can capture the imagination to the extent that people ascribe them significance, reminding us that belief in sacred geometry is very much alive today. Both sites, regardless of one’s level of skepticism, challenge us to keep an open yet critical mind about the link between shape, place, and unseen forces.

Conclusion

Palmanova, Italy, stands as a unique crossroads of history, geometry, and mystery. Its perfectly star-shaped form – born from the ingenuity of Renaissance military architects – has proven enduringly captivating. On one level, Palmanova is the pinnacle of rational design: a fortress-city built to embody utopian ideals of order and to withstand the warfare of its time. We traced its historical arc from a Venetian bulwark of the 1590s through Napoleonic and Austrian eras to its modern status as a UNESCO World Heritage site. On another level, beneath the surface of dates and wars, Palmanova hints at deeper currents: sacred geometry, numerological symbolism, and geomantic intent. The obsessive recurrence of the number 3 in its layout and the protective water moat around its heart suggest that its creators sought to craft not only a defensive stronghold but a kind of harmonic space – a bastion of both material and spiritual security.

Exploring Palmanova through an esoteric lens, we found intriguing associations. The star fort’s geometry resonates with concepts of ley lines and earth energy grids that some modern theorists propose; although no scientific anomalies have been recorded, the very completeness of Palmanova’s design invites speculation that it might sit at a special energetic node or create a field of influence by virtue of its shape. We saw how local lore and alternative researchers have, over time, layered the site with legends: ghostly soldiers on its ramparts, Masonic meanings in its measurements, even fanciful links to solfeggio frequencies and global conspiracies. Such interpretations, while unproven, enrich the narrative of Palmanova as more than an artifact – they make it a living symbol open to new meanings in each era.

When placed alongside the case of the Bosnian pyramids of Visoko, Palmanova’s story becomes part of a larger human saga: the drive to connect geometric forms with cosmic powers. Both in Palmanova’s deliberate star and Visoko’s alleged pyramid complex, we see the interplay of skepticism and belief, science and myth. Each site magnifies the question of whether certain shapes can channel energies or consciousness – be it the focused defensive “chi” of a fortress or the healing vibrations of a pyramid. Palmanova, with its well-documented construction, provides a reassuring example that advanced geometry has been deployed by societies for concrete purposes (and possibly symbolic ones); Visoko’s controversial hills remind us to keep questioning how much we truly know about the intentions of builders long gone – or the secrets that natural landforms might hold.

Key to our deep dive was the context of the Palmanova-Udine region, which has proven rich in noteworthy individuals and endeavors straddling the worlds of military, scientific, and mystical pursuit. Figures like Giulio Savorgnan and Carlo Rubbia illustrate a continuity of innovation in this corner of the world: from designing ideal cities to discovering fundamental particles. Likewise, the folklore of the Benandanti and the modern creative hypotheses of energy-sensitive visitors indicate a persistent vein of spiritual curiosity in the local culture. Even the name “Udine” itself, though likely meaning “hill,” became a canvas for speculative meaning – connecting to Odin’s energy, undine spirits, and the notion of consuming or transmuting energy. This exercise showed how a toponym can inspire narratives about the “soul of a place,” and Udine’s soul appears to be one of resilience and nourishment, much as Palmanova’s form is one of protection and harmony.

In conclusion, Palmanova’s star continues to shine in multiple domains of understanding. Historically, it is a triumph of Renaissance urban planning and a fascinating example of how fear (of invasion) can produce beauty (in design). Geometrically, it is a testament to the power of shape to impose order – a power that extends psychologically to those who experience the city. Esoterically, Palmanova invites us to ponder the relationship between human intention, mathematics, and the ineffable qualities of place. Whether one stands in the quiet central piazza at dusk, or views an image of the nine-pointed fortress from space, there is a palpable sense of a grand design at work – one that operates on physical, intellectual, and perhaps even spiritual planes.