Stern Gerlach Experiment seems to evidence Discrete Quantum Mechanics but

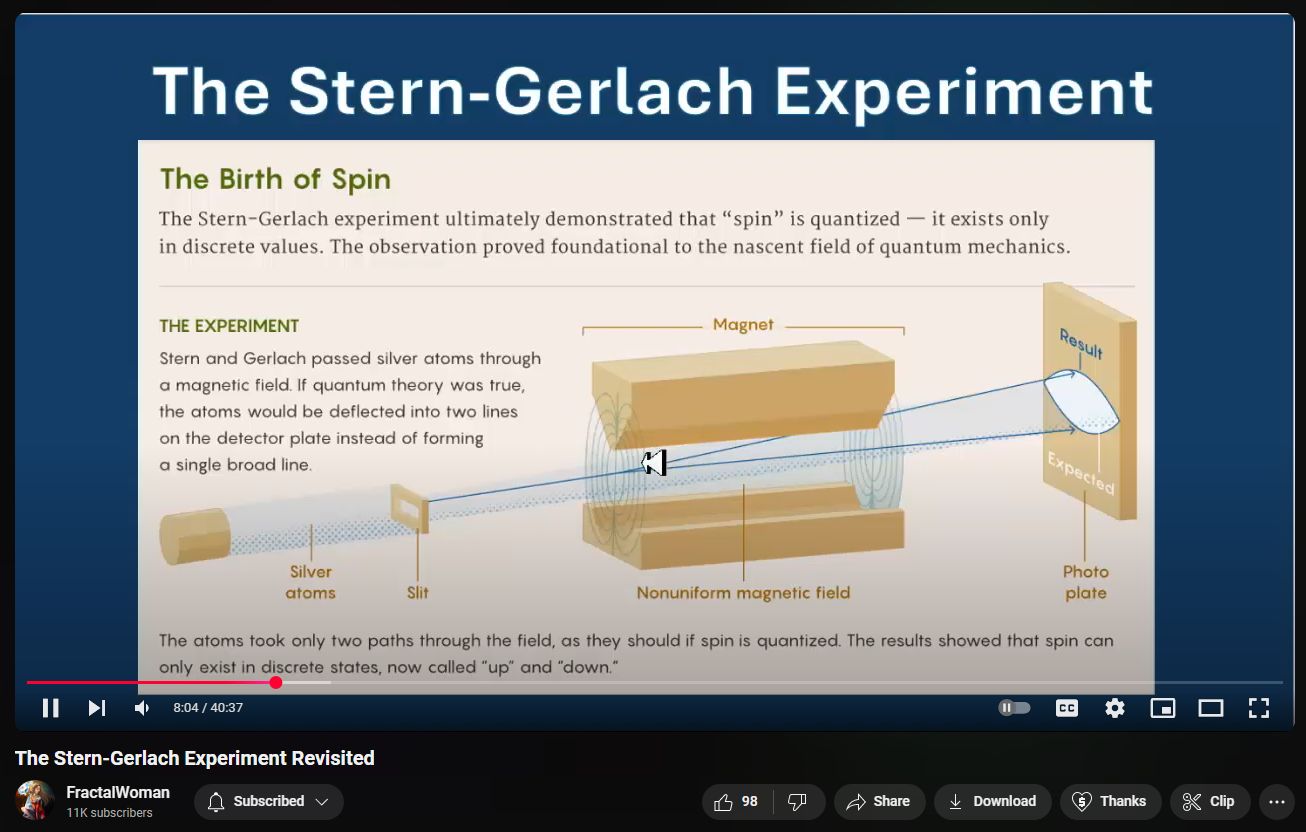

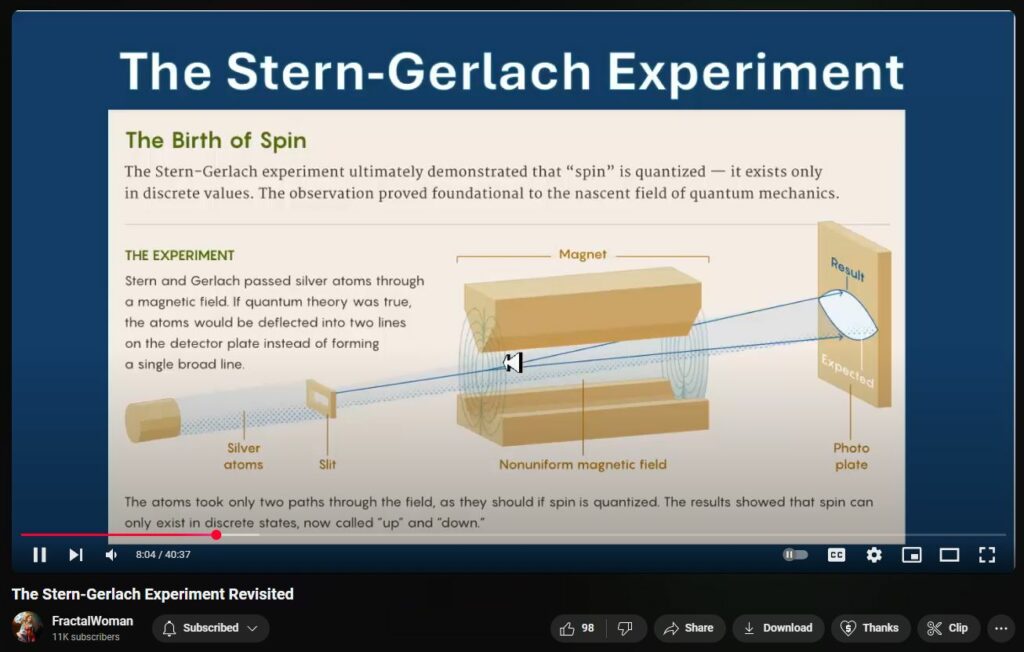

The shapes of the magnets (and thus the field geometries) are radically unequal.

Ken Wheeler’s “dielectric inertial plane” exists at the center of the magnetic field.

Outstanding presentation of the Gerlach and Stern experiment. On the comment of balabuyew, writing that the experiment requires a non uniform magnetic field, I would point out that the simulation shown by FractalWoman in her geometry simulation is by defacto an inhomogeneous simulation. In addition reading about the G & S experiment (Modern Atomic and Nuclear Physics) on page 105 : “But the fact that only two deflections exist, corresponding to the maximum amount of deflection expected in either direction, shows the quantized nature of the orientation of spin” would be as mathematicians say : A necessary but not sufficient condition to claim absolutely the quantized nature of the orientation of spin.

I’ve come to distrust and be very skeptical of experiments that purport to show things like quantum mechanics or claim to prove the electron is a particle. I think the main problem is our inability to directly observe on the scale of individual atoms. Because of that deficiency, we’re forced to interpret experiments results in a way that may not represent what’s actually going on.

Nature itself resists quantization. All values are arbitrary, leaving us to discern based on proportion and time. Like op video, the field of the magnet is one over phi, forming loops of egg shaped objects. We then attempt to find spot values or quantize the entire field object even though from another perspective the magnet is an object reflecting the shape of the universe, extending to infinity in all directions.

It’s really logical that measurement changes the system because like you said, you have to inject energy, maybe send a photon to excite an electron, etc. Also in my opinion the term ‘uncertainty’ puts the wrong idea into ones head. What it actually represents is the standard deviation of measurements. If you prepared 100 same states and measured each one, you will get different results with some probability, and the ‘uncertainty’ is the deviation of said measurement results.

Once again, excellent work. I know that you are a big fan of Ken Wheelers and he has some interesting insights, but he is a bit of a wackadoo. You, on the other hand, have a structured, scientific, can I say ‘mathematical’ approach to your work when, combined with insights that ‘buck’ the indoctrinations of academia, is extremely refreshing and oddly consistent. My opinion: you should work on building your brand. You ought to have 1MM followers by now. I am studying your X standards and I am WAY on board with what you are doing with that. It has helped me with a time domain definition I have been working on, (for like decades). Thank you!

The problem with your analysis is that if instead of silver with total spin 1/2 you use an atom with a total spin of 1, you get three lines in the SG experiment instead of two, and the third will be directly in the middle, which your model doesn’t explain. [Did they actually do this experiment? If so, can you point me to a source? Thanks in advance.]

Hello FractalWoman i love your journey of reconstructing physics on your own, and you are very close to finding “quantum” in this experiment analysis. Your classical physics intuition is spot on, all ball dipoles will move like you say, aligned in a vertical line north to south caught by “orbitals” as you said. Since dipoles start at random orientation some will be on their sides and they will need some minuscule time to reorient to magnetic field so they will hit the wall closer to the middle, the ones oriented vertically at start will hit the wall farthest from the middle, so they will form a vertical line hitting the wall, and that HAPPENS in real life with small test dipoles and most atoms, they form a line north to south. BUT SILVER with 1 electron in last orbital form only top and bottom points, nothing in the middle, no matter how they start oriented. And that is what is strange in SG experiment. Why are they hitting the same vertical distance above or below the middle point no matter how they started oriented? And why only atoms with 1 electron in last orbit do this? The rabbit hole starts here.

The reason they choose atoms with one electron in the last orbit is so that there is a Dipole moment (and not a Quadrapole moment or some other configuration). Regarding your question, I believe I answered that question when I compared the isopotential field diagrams with the probability distributions of the electrons inside an atom. There is a low probability of finding an “electron” in the region exactly between the N and S pole and there is a higher probability of finding them both above and below the low probability region. Now, it’s possible that I am wrong about everything I am saying here. But until we do the SG-Experiment using two permanent magnets with the same shape and size, I will still be suspicious of the mainstream INTERPRETAION of this experiment.

The silver atoms derive their magnetic dipole from a significant angular momentum relative to their mass, which gyroscopically resists being changed. This angular momentum is established before they enter the vicinity of the magnet.

You never use the fact that the Stern-Gerlach Experiment specifically requires non-uniform (!) magnetic field. So, all your logic is wrong.

@FractalWoman1 day agoThe two magnets in my video do form a non-uniform magnetic field between the magnets. In fact, even if the two permanent magnets were exactly the same, there would still be a non-uniform magnetic field between the two magnets. https://chatgpt.com/share/67963bd4-1e1c-800a-94fa-1827df9d7817 You can easily see this when looking at the isopotential gradients that form between the magnets. Interestingly, THEY never did the experiment with two permanent magnets that are the exactly the same. https://chatgpt.com/share/6793acfc-ac8c-800a-addd-49d5cb7eac7c I would like to see that experiment. What THEY didn’t take into consideration are the isopotential “orbits” that the tiny dipole moments would follow because they are moving at some velocity. They also have no way of proving that the magnetic moments anti-align. This is just an assumption they made based on their potentially flawed logic.

The Stern–Gerlach experiment, conducted in 1922 by Otto Stern and Walther Gerlach, provided pivotal evidence for the quantization of angular momentum, a cornerstone of quantum mechanics. In this experiment, a beam of silver atoms was passed through a non-uniform magnetic field, resulting in the beam splitting into two distinct paths. This outcome demonstrated that certain physical properties, such as the component of angular momentum along the magnetic field direction, can only take on discrete values. (Physics World)

The article from 4Science.org titled “Stern–Gerlach Experiment Seems to Evidence Discrete Quantum Mechanics, But…” appears to delve into the implications of the Stern–Gerlach experiment concerning the discrete nature of quantum mechanics. While the experiment is traditionally interpreted as evidence of discrete quantum states, the article may explore alternative interpretations or limitations of this conclusion.

It’s important to note that the Stern–Gerlach experiment has been extensively analyzed and remains a fundamental demonstration of quantum mechanics. However, ongoing discussions and analyses continue to explore its nuances and implications, contributing to a deeper understanding of quantum theory.

For a comprehensive overview of the Stern–Gerlach experiment and its significance in quantum mechanics, you may refer to the following resource:

This source provides detailed insights into the experiment’s methodology, findings, and its role in shaping modern physics.